Canada's First Tech Company - Microsystems International (MIL)

Matt Roberts's Newsletter - Issue 1

Hey there,

You might have forgotten you signed up for my newsletter, I didn’t, but things got strangely busy over the past 6 months. And the ScaleUP portfolio has been in the thick of it.

Just to do the VC thing and take credit for other peoples hard work. On my end:

While my colleagues worked with RoseRocket, Savvyy, Coconut, Nylas and Dooly to help get their funding rounds completed.

All since June.

Crazy busy times… and because of that, hard to find time to share thoughtful viewpoints outside of the daily noise.

But now that things on my end have seemingly slowed down, I feel like it’s time to dust off the idea of my newsletter.

Going forward I’ll be sharing links and thoughts primarily on the Canadian tech and venture landscape. But also when time permits some longer form Canadian tech history. I’ll still do the occasional tweet storm, but sometimes I’ll just need more space to share.

To start, I thought I would share the story that I believe pinpoints the start of Canada’s tech industry. If the history of Silicon Valley starts with the traitorous eight and the ‘fairchildren.’ Then I’d say that the story of Canada’s tech industry starts with a little known company named MicroSystems International Ltd (MIL).

I hope you enjoy this and thanks for subscribing!

matt

- Matt@ChapeauCapital.com

The birth of Canada’s tech industry

MicroSystems International Inc.

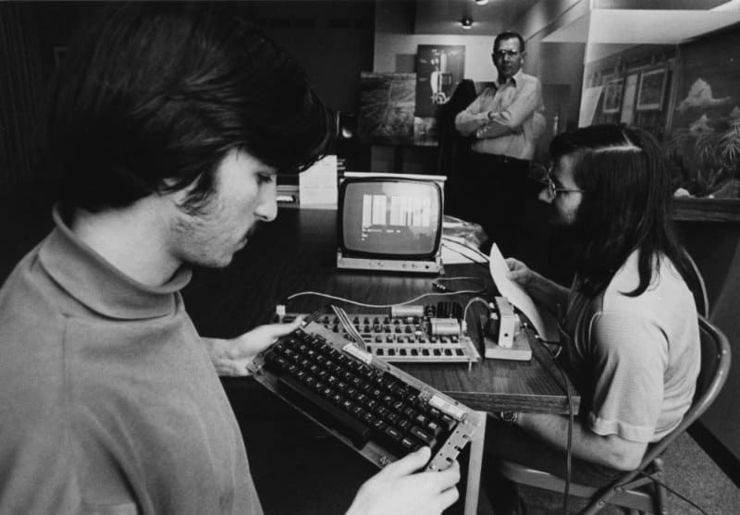

In the spring of 1975, a young and shy engineer from Hewlett Packard attended his first computer club meeting in California.

Writing years later he said:

I was scared and not feeling like I belonged, but one very lucky thing happened. A guy started passing out these data sheets - technical specifications - for a microprocessor … from a company in Canada… I took it home, figuring, ‘Well, at least I’ll learn something.’

That night, I checked out the microprocessor data sheet ... I realized that all I needed was this Canadian processor with some memory chips. Then I’d have the computer I’d always wanted! ... I could build my own computer, a computer I could own and design to do any neat things I wanted to do with it for the rest of my life.

That engineer was Steve Wozniak. He co-founded Apple. He designed the first widely accepted personal computer. He could have designed that computer with a Canadian Microprocessor. But it never happened.

Why it didn’t is the story of Microsystems International Ltd. (MIL), Canada’s plan to build a domestic semiconductor industry.

Missing the future

That plan started in the offices of the Canadian Government in Ottawa in 1966.

The Federal government released a report on tech that sounds eerily like it could have been written yesterday. It complained that the lack of investment in manufacturing and R&D for tech (specifically computers) was damaging Canada’s competitiveness.

Particularly, retention of students graduating with technical skills was low (brain drain), foreign interests were hiring Canadian talent thus leveraging their technical discoveries (loss of IP), and there was a large dependence on foreign companies for tech products.

The TLDR of the report is that Canada was missing the boat on computers but it had a chance to be out in front on semiconductors as computers switched from older technology. The action plan was that Canada should double down on this industry with capital investment. But the Ministry of Industry (today Industry Canada) had learned some lessons trying something like this before, when it tried to create a Canadian aerospace industry (today known as a small boondoggle called the Avro Arrow program).

The Arrow is not today’s story. They had learned that Canada was too small to entirely carry a domestically focused industry (as had been in the case of the Arrow initially).

With that learning, they aimed to find a partner that would setup manufacturing and design operations in Canada. The partner also had to have either a need for the semiconductors themselves or who knew who to sell them to outside of the country; the federal government would not be the end customer, it would be the investment partner. Canada was going to export its way to success.

It took two years to find that partner.

Just around the corner

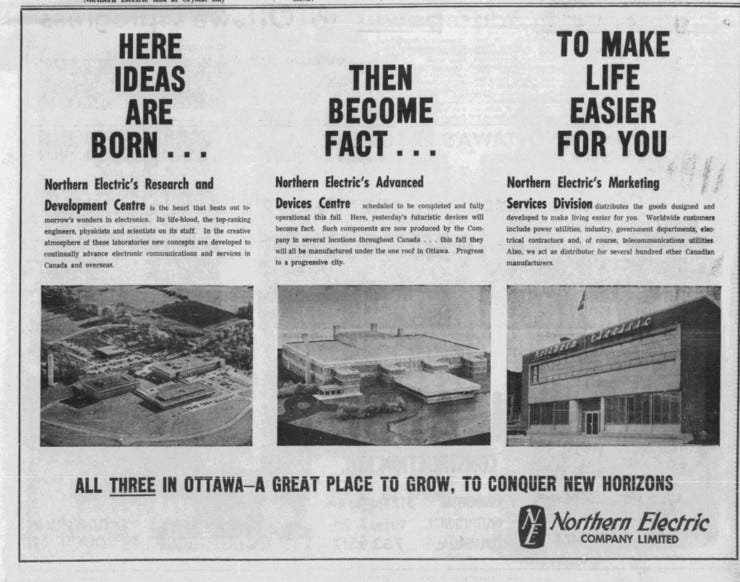

Several international candidates were discussed and approached, but in the end, the answer was seemingly just down the road in Montreal: Bell Canada and its subsidiary, Northern Electric Co, which was later known as Bell Northern Research, or Northern Telecom, and eventually rebranded to its last incarnation in the 90’s, Nortel. The government had tried other foreign partners, and been turned down - but with Northern and Bell, it felt they had met the right partners. Plus, they were Canadian!

Northern Telecom had been experimenting with designing its own semiconductors and small scale manufacturing but had not built any high-volume manufacturing systems. A Fab, or Semiconductor Fabrication Plant (essentially a factory), was an ingredient the government felt was key to a successful Canadian semiconductor industry. So in 1968 the government ‘incentivized’ Northern and Bell to spin out their ‘Advanced Devices Group’ into a separate company.

Management of the company would be in Montreal, while its technical operations were located in Ottawa. Importantly, this would create significant tensions and later outright hostility. This is also when the company got the name Microsystem International Ltd (MIL).

Unfortunately the company was already behind its competitors the day it was founded.

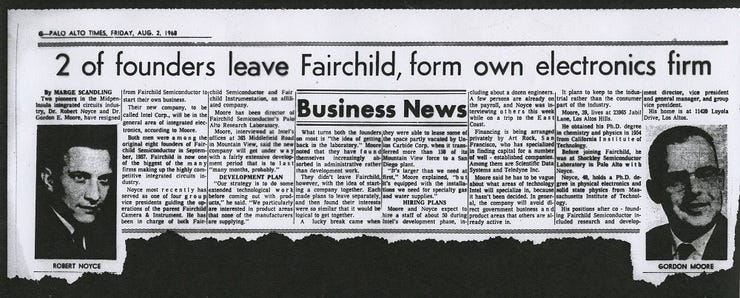

In 1968-9, semiconductor manufacturing underwent a huge revolution in how they were manufactured, and the technology MIL inherited from Northern Electric was of the older variety. If the company wished to compete, it needed to get the new semiconductor fabrication processes, but only two companies had them. One was Fairchild Semiconductor, which refused to work with the Canadians. The other was a small group of a few dozen or so engineers who had left Fairchild to start their own firm. You may have heard of them: that company was Intel.

A Match Made in Heaven

Although founded only a few months earlier, the company was a dream team of semiconductor pioneers. Beyond thinking about the next generation memory chips, Intel was also innovating on the microprocessors front.

MIL and Intel was a match made in heaven.

Under the terms of the agreement between MIL and Intel, the Canadian company was to get the rights to build their own version of Intel’s fabrication process (MOS silicon-gate technology), the right to produce Intel's existing chips on it and sell them (second-source rights to Intel’s semiconductor memories). Intel would set up the production line at MIL’s Ottawa facility and guarantee the quality performance of the fabrication process.

You heard this correctly: Intel’s second Fab ever was in Ottawa, owned by MIL but run with Intel’s help. If you were to read every Intel history book (I think I have)…. they never mention this.

With this deal, Intel licensed nearly all of its memory chip designs to MIL, allowing them to compete with the major players in the market. The federal government had what it wanted: Microsystems International had now leapfrogged to one of the top semiconductor firms in the world.

But how? How did MIL get this done?

With money of course, lots and lots of money.

$93,392,000 to be exact.

But that was in 1970.

Today that would be $670,639,035.18.

You read that right: MIL received $670 million to get started.

Let's break down where it all came from.

First the company IPO’d, raising $18.7 million from the public. How did they IPO? With the help of Bell, who promoted the opportunity: if you bought one Bell share you also got a MIL share for your trouble.

Northern Electric cosigned a loan for $10 million and provided a line of credit for $12 million. And the federal government provided grants and interest free loans for $35 million(!).

The rest came in the form of guaranteed loans or “in kind loans’ from Northern Electric.

What did the company spend this money on?

Getting Talent

At first, staff and lots of them. Manufacturing and designing semiconductors at this time was labour-intensive work. By 1970, the company employed 1200 people and was on track to hit 3000 by 1972.

Similar to today, talent was a problem, and MIL couldn’t find it all locally.

Mostly because, at this time, universities in Canada were graduating fewer than a few hundred people who focused on microelectronics. So MIL went on a world wide hiring spree. European universities were inundated by MIL recruitment teams. Of a 1970 graduating class of 27 from the University of Cardiff, 14 ended up at MIL in Ottawa. Students from the UK were highly-sought, graduates from tier-2 US technical schools were also hired - Rochester Institute of Technology (initially a Kodak preserve) saw 10 graduates arrive in Ottawa in 1971.

European competitors were raided as well; Canada’s currency was pegged at a high value (i.e. the $ was artificially equal to the U.S. Dollar) at the time, and thus at a very high conversion to the European currencies. Experienced technical staff from Siemens, Marconi and others were all enticed to move to Canada for salaries much higher than they were getting at home. Employees also believed they were joining a cutting-edge future world player in semiconductors.

To the governments relief, the semiconductor brain drain began reversing.

Building a microprocessor

By 1971, the ingredients were all there. MIL had staff, they had a fab, they had customers - Northern and Bell said they would buy their stuff while the world market for memory semiconductors was growing. But they didn’t have a microprocessor. The second part of the Intel-MILpartnership was to build one.

At this time, Intel was designing not one, but two, and with MIL’s support, they would build a third.

In the early 70’s, most semiconductors were then primarily meant for calculators, which were shrinking from room-sized machines to desktop (and soon portable) sizes.

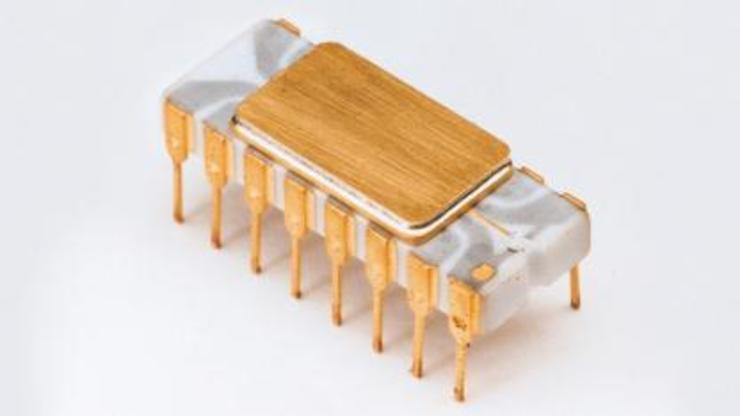

Intel had a customer (Busicom) paying it to design a newer chipset for a calculator. Usually this required 8-10 chips, but Intel gambled that it could make it all on one multipurpose chip (with most of the RAM And ROM built in). That way, the company could charge half as much and make way more as the manufacturing of the actual chip was pretty cheap. This one-chip potential solution was codenamed the 4004 (as it had 4 bits).

Intel was also working on another chip named the 8008 that was even more advanced, but that was at least two or three years away and was mostly a dream in 1971.

The 4004 design would be cutting edge - possibly to the point that Intel’s current manufacturing process might not be able to make it. So, worried it might fail, Intel did what any good startup would do: it hedged.

And when MIL came along wanting to build a microprocessor, that hedge was developed with MIL.

Codenamed the 4005, the chip was a meat-and-potato design. It would also be easier to manufacture, as the RAM and ROM would be separate from the chip.

MIL wanted to learn how to design and develop a microprocessor, which was great for Intel - the company was having trouble finding design staff. So MIL would design it and Intel would help manufacture it - which was great because MIL didn’t know how to do that. It was also pretty much guaranteed to work.

By 1971, however, Intel had solved every major technical challenge with the 4004. And on the wikipedia page for the 4004 is the listing of all the Intel 4004 support chips: 4001, 4002, 4003, 4008, and 4009. Notice that jump in numbers? Where is the 4005?

Well, Intel didn’t need it anymore. The 4004 was a game-changer and Intel knew it.

A brief aside: these deals with MIL were huge for Intel, but not one Intel history book mentions it. Why was it such a big deal?l MIL paid Intel for the company’s help $2 million plus royalties going forward. In 1971, Intel had its first profit - all due to payments from MIL.

In 1972, MIL went ahead with its own 4005 Chip (named the MF7114, with Intel still helping on production), but now in a market with a massively innovative next-gen chip that was both better and cheaper.

You might think this was stupid - but there is a logic behind the decision. MIL wanted to learn how to design and build a chip by itself, and with the MF7114, they had done both . The company also believed it had a customer in both of its parent companies (Bell and Northern Electric). The chip was meant mostly for their use. This was the first chip - not the one to bet the company on, but to build the experience and knowledge internally to design future chips.

Bul MIL’s timing sucked. The MF7114 launched just as the semiconductor market imploded.

The start of a semiconductor boom-and-bust period began in 1970 and MIL walked right into it. It became known as “the Calculator Wars.”

A ‘brutal industry’

By 1971, semiconductor manufacturing capacity in the industry was growing as dozens of international firms (almost all with government-backed loans to build Fabs) needed to keep those factories humming or lose money. So chip manufacturers licensed integrated circuits and memory chips and pumped them out. Just like MIL was doing.

Unsurprisingly, prices collapsed as the market demand was saturated. And remember how Intel’s 4004 needed less memory semiconductors? That just exacerbated the problem.

The price collapse coupled with governments incentivizing domestic systems integrators to use locally sourced chips instead of foreign ones meant that semiconductor manufacturers without large domestic markets found themselves with a problem: no one would buy their chips unless they were heavily discounted.

The best example of this was in Japan, where most calculators were built and manufactured. Nearly all of Japan’s semiconductors were foreign-made (over 50% by 1973), mostly due to international semiconductor companies pumping out chips at a loss and sending them overseas. Japan amalgamated most of its semiconductor manufacturing and started a campaign named (you can’t make this up) “*You can’t trust foreigners*” trying to convince SHARP and others to only use domestic components. This focus helped build Japan into a powerhouse of semiconductors: all the Quartz watches and technology from Japan in the 70's and 80’s started with a focus on making sure the domestic system integrator market used locally sourced chips. And if they didn’t, the government wouldn’t buy anything from them or lend them money. Germany did this to a lesser extent, as did Britain and France.

This hurt Northern Electric's relationship with MIL because Europe was the primary non-Canadian market for its equipment. Those countries were demanding locally sourced chips for their telecom equipment to the extent that companies opened factories to receive equipment without the semiconductors and then installed the local ones to meet the government demands.

The Canadian government tried initially to do the same. IBM is a clear example: just outside Toronto, IBM built ‘Canadian’ Computers with locally sourced semiconductors to get the government business. Where were those locally sourced semiconductors coming from? Bromont, Quebec, where there is still an IBM Fab (along multiple others). But much of the actual intellectual property was and remained American.

Northern’s betrayal

Worse still, MIL’s crowning achievement, the MF711chip was orphaned. Northern Electric introduced the first Computerized Telephone Exchange Switch - it was a game changer and would cement Northern as a global manufacturer. Named the SP-1, it was meant to use the MF711. What chips did it use? Why, of course, the Intel 4004.

How this happened, pardon the pun, is due to a game of telephone.

Northern spec’d a design that it told MIL would meet its needs, and MIL delivered it. But no one told the SP-1 team that it had to use the MIL chips. So when the SP-1 design team saw a chip that was cheaper to integrate, versus the MIL chips, they used that.

Why didn’t the federal government tell Northern to use MIL chips? Well, it did. Remember that licensing agreement with Intel? Intel licensed the 4004 to MIL to make in Canada. But Intel got a royalty off each one, erasing the profit for MIL.

MIL now had a chip with no customers. The company tried to pivot, branding the MF7114 as a calculator chip, but it didn’t work.

During this moment in time,one of the most famous stories of MIL occured, which is how I learned about the company.

Two young British engineers in their 20’s, fed up with the MIL bureaucracy and its inability to make decisions, decided to quit. They knew the chips for SP-1 inside and out and decided to leave MIL to build their own solutions they could sell to SP-1 clients. Their names were Terry Matthews and Michael Cowpland and they founded a company named Mitel.

The beginning of the end

In 1971, MIL announced $12 million in losses for the 21 months of its existence, on sales of about $12 million - what those losses did not include was another $10 million worth of direct R&D costs. Who paid that? The Federal Government. So really, it was $22 million in losses for $12 million in sales.

The Montréal head office, which was down the street from Northern Electrics, believed that MIL’s Ottawa Operations were a mess. In their mind MIL had built a chip no one wanted, and it was bleeding red ink. MIL’s technical leadership wanted to build a new microprocessor to compete with Intel and stop building semiconductors mostly spec’d for Northern.

This new focus made no sense to Northern. So it 'fired' MIL’s CEO, moved the head office into Northern’s building, and laid off significant portions of the original microprocessor team

From this point on, MIL was treated as a Northern subsidiary. (even the logo changed)

The company built chips predominantly for domestic Canadian consumption. Chips that Northern could get excellent pricing for because the Canadian government was providing a tax subsidy for each one made. The manufacturing Fabs and memory design teams were retained. But all talk of new microprocessor design was ended and when Intel released the first 8-bit chip in 1972, the 8008, MIL was the first company to license making it.

And that, in fact, was what MIL became famous for: making other versions of Intel chips. When Steve Wozniak was at the computer club in 1975, he was looking at a brochure for a MIL-branded Intel 8080 chip. Made in Canada, designed in California.

But the company couldn’t compete, at least not without government subsidies, which ran out in late 1974. By 1973, the company had used at least $24 million worth of subsidies and loans (the last number I could find).

Now that the government’s subsidy support had run out, Northern bought the whole company. Why?

Tax losses!

Which Bell and Northern could use. But in this period, tax loses expire within five years and getting them in 1974 was important (as the company was founded in 1969). These losses amounted to $43 million in 1970, about $350 million in today’s money. It was also more than Bell or Northern made in profit that year. So not only did the government lose money on loans and subsidies, the guys who ran it into the ground picked up the tax losses (and equipment) for pennies on the dollar.

Post-1975

The aftermath post-MIL for the semiconductor industry in Canada is actually a pretty good story - it just didn’t look like the industry that the government had set out to build in 1968.

Vernon Masquez (the Chairman of Northern) said later that Northern had gotten into the chip making business against “its better instincts.”

Which was probably true.

Mike Cowpland said it was “terrible Management. They were going from a monopoly to the world’s most ruthless industry” and that they weren’t prepared.

That’s probably true.

Terry Matthews once told me the biggest lesson he learned was that a customer isn’t a customer until he pays. And Northern was never really the customer it promised to be.

That is definitely true.

The federal government was urged by the opposition in 1975 to conduct an inquiry into the mess. This was the biggest investment in tech by the Pierre Elliott Trudeau government, and the opposition, led by the NDP, wanted to know what had happened to all the money. The Liberals said, “no inquiry was needed.”

I’m not so sure that was true.

But what lessons should we take from this? Should we call it the story of government waste and mismanagement, with Nortel in the mix?

If the story stopped after 1975, then yes, it was an unmitigated disaster.

Looking at the story 20 years later, in 1995, you might think differently.

By then, over 90 companies had been founded or co-founded by former MIL employees, many of them only in Canada because they were recruited from around the world to work there. Those companies were worth over an estimated $3 Billion in 1995 and would be worth several times that by 2000. Newbridge, Corel, Mosaid, Chipworks, JDS, Tundra, Mitel, Cadence Computers, Calian, Crosskeys, etc., all trace their founding teams or first employees to MIL. Canada’s first venture capital investments were into former MIL employees. And the tech industry was built on the back of that employee network. Canada’s first tech angel networks were founded by former MIL employees, who founded their companies in the 1980’s.

And Northern Electric? Well in 1979 they announced they would be making chips for themselves in Ottawa - because the talent was still there. They were back in the semiconductor business.

Today, Microsystems International Ltd. is completely forgotten, or a footnote at best - there is not one history book written on it. When Nortel’s history was written by Peter Newman (paid for by Nortel) he devoted 5 lines to it. But in reality, it was this company more than any other that began Canada’s push to the front of the line in tech. We should remember the hard-earned lessons from it and respect the work done. Otherwise, we’ll experience a mess like this again.

Some thanks is due:

I'd like to thank Douglas, David, Ami, Laith, Steve, Chris & Mike who all read this over a few times for clarity. Where it doesn't make sense it's my fault. Where it does, thank them.

I spoke to a half dozen former Nortel and Microsystems staff asking them for their memories. While no recollections are perfect they all had some insights on where and how the Northern & MIL relationship soured, which is very hard to discern as the leadership of both groups never wrote down their deep thoughts. I don't think we'll ever know for sure exactly what boardroom politics took place.

There is one historian who has covered some of this story - Zbigniew Stackniak - an Associate professor of Computer Science at York University he also runs the York University Computer Museum. His paper on MF7114 is treasure trove for chip nerds like myself.

Also Revue doesn't allow me to share citations - as former history student I'm gutted it doesn't - regardless if you anyone is looking for some of the rabbit holes for this feel free to reach out.