Who killed Canadian Venture?

We might have an economic serial killer on our hands...

This is a long post, but I believe worth it.

One of the unique things about getting older is seeing how some things can have second-and third-order effects over time. As an amateur historian, I find these effects much easier to see. However, seeing them within one’s lifetime or career is fascinating because sometimes you wonder why no one else talks about them. What is often surprising is how you notice that people in your industry don’t know, remember, or perhaps care all that much.

Take, for example, my previous post on the ‘Missing Canadian Dotcom Crash.’ It was not news to my VC friends of my vintage or those who preceded me in the Canadian VC field. However, it was news to many newcomers, including people working in Government or at the BDC and CVCA; in both cases, members of their board of directors and committees reached out and, notably, throughout the VC field of people who joined us in the business post-2013 or so. It wasn’t an age thing, but the vintage of when you joined Venture as a vocation created this knowledge gap.

The question from those who didn’t know its history or live through it was, primarily, why? What killed Venture off during those years…

Was it bad returns? Bad VCs? or a terrible local market for investments?

You can, and people did, place blame on those attributes—but one central pillar of a healthy PE or VC ecosystem disappeared. It was when our traditional LPs abandoned Canada.

Let’s set the stage and dive into what happened because it’s surprisingly timely. There is something of a policy debate going on.

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith wants to leave Canada’s Pensions Plan (CPP). And not without something on the way out:

One highly controversial aspect of Alberta’s pension initiative is that on leaving the national pension plan, the province claims it will be owed 53 percent (or $334 billion) of the estimated total assets of $575 billion held by the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB). Alberta represents about 15 percent of the people who contribute to CPP.

This is a unique proposition.

Secondly, in the 2023 November Fiscal update:

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland’s fall economic statement was more interesting than she indicated it would be. She is considering a rethink of Canada’s approach to retirement by working “collaboratively” with Canadian pension funds to encourage them to invest more in Canada.

Then, a week or two back in March of 2024, we had this:

Almost 100 top Canadian business leaders have signed an open letter to Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland and her provincial counterparts, urging them to change investment rules for pension funds to “encourage them to invest in Canada.”

The letter, published as an advertisement in major Canadian newspapers on Wednesday, included signatures from Rogers Communications Inc. CEO Tony Staffieri and Canaccord Genuity Group Inc. CEO Dan Daviau. Of the current CEOs of the country’s six largest banks, National Bank of Canada’s Laurent Ferreira was the only one to add his name to the letter.

The Pensions and their supporters got organized and responded with what was initially:

Many pension-fund leaders are quietly worried that adding more exposure to Canada would increase concentration risks, as the future solvency of plans is already correlated to the country’s demographics, economic growth and immigration policies, among other factors.

The CEO of Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System, Blake Hutcheson, said the fund manager – which invests $129-billion on behalf of 600,000 Ontario public-service workers – is “dedicated to growing and fiercely defending their retirement savings,” in an e-mailed statement. “We must put members’ interests first and foremost, above those of any self-interested parties with competing agendas.”

and

“You’ve got to create the opportunities,” said Jim Leech, former CEO of Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, which now manages $250-billion. “It isn’t forcing or enticing people into Canadian investments, it’s providing sufficient good investments in Canada.”

There was one contrasting statement I’d like to highlight.

Healthcare of Ontario Pension Plan (HOOPP) chief investment officer Michael Wissell said in a statement that, “all else being equal, we prefer to invest in Canada when the risk and reward are appropriate.”

These are all unique views, and I’ll come back to them.

Welcome to policy sausage making. It is rare in Canada, but you’re seeing almost in real time that the Wellington and Bay Street discussions on Canada’s Pension Plans, which used to be held behind closed doors or over the occasional lunch meeting, are now more of a public debate.

No one agrees precisely, and the disagreement among our Political and Financial leaders is now public. Get some popcorn.

This is not new; I’ve heard about it for most of my career, but it is entering more of the public realm.

But how did we get here?

An abridged history of the Canada Pension Plan

Let me set the scene for those who don’t follow the Canadian pension plans and their histories. The Diefenbaker government initiated the work leading up to the 1966 introduction of the CPP and using it as a fundamental part of Canada's social safety net.

For three decades, the CPP has been a “pay-as-you-go” plan. Premiums only provided a fund equal to two years of benefits. So, the cash went in, and within a few years, the cash went out. By 1992, that system had begun to fall apart, and the pay-in and pay-out mechanisms were on the verge of no longer functioning. The CPP had been investing in Government bonds and other less-than-stellar investments; the CPP had assets but was in danger of becoming insolvent. This all culminated in 1995 with a damning report by Canada’s Chief Actuary (yeah, we have one). Don’t click that link; here’s the TLDR:

In a lot of actuarial jargon, the report says that CPP can only be counted on if premiums rise dramatically and that the pension people expected would be gone by 2010. It could be even worse with the expected demographics (fewer kids, etc). We needed to fix it.

So by 1996/1997, there was only $40 billion in that Fund, while the cost of promised future benefits totalled $600 billion. Without changes to the overall plan, premiums on individuals would rise to 14.2% of pensionable earnings by 2030.

This was an impetus for a significant overhaul.

In 1997, Ottawa and the provinces agreed to two significant changes to the CPP.

The first was to increase premiums from about 6% more rapidly than planned but to cap them at 9.9% by 2003, which would be 4.95% for employees and 4.95% for employers. This equalled an $11 billion increase in annual premium revenues. At the expected inflation growth rate (Inflation +3% or so), this would make the plan short-term solvent and sustainable over the long run.

Second, benefits were calculated differently, slightly reducing the pensions of new beneficiaries, the death benefit, and the ability to get disability benefits.

So, if, like me, you were an 18-year-old that year working full-time. The Government asked you to pay a lot more, and you’d get less than others had received in the past. If millennials or GenZ reading this feel hard done by previous generations - remember it started with those of us in GenX getting a bit screwed by the boomers.

A significant change alongside this new CPP fee increase was the attempt to depoliticize CPP’s investment decisions. They added two new letters to the acronym, IB, and subtly implied they were one and the same. CPPIB was born. That IB was essential to the Canada Pension Plan and Investment Board. The Board would consist of quasi-independent directors who all had to have backgrounds in Finance or economics or business… this was important stuff. Before, ex-politicians and political donors were sometimes on the board, and their interests were more aligned with increasing their personal standing, not the results of the CPP. No longer would this be the case.

Not allowing them to go completely off with our money without public scrutiny of the CPPIB, the legislation required the ten provincial finance ministers and their federal colleagues to review the CPPIB's mandate and regulations every three years. The CPPIB is also subject to a special examination every six years by an auditor appointed by the Federal Minister of Finance.

The CPPIB is trying to remind Canadians of this part of their history and has a friendly (to them) discussion of all this on the CPP website. When was it written? Just after Minister Freeland began discussing getting CPP to invest more in Canada, it was back in November.

That history has a small aside that, if you miss it, may not seem important:

“In 2006, CPP Investments decided to adopt an active management strategy to help improve overall returns for the CPP Fund. This decision enabled our investors to seek out opportunities for above-market returns over the long term in an effort to manage the Fund in the best interests of contributors and beneficiaries.”

What isn’t mentioned in the CPPIB’s history or most CPP discussions is that there was a Canadian content rule when the 1997 legislation was enacted. 80% of all investments had to be made in Canada, and 20% could be made internationally.

CPPIB and their pension colleagues begged, cajoled, and ultimately lobbied for a change to the 80-20 rule, which was eventually adjusted to a 70-30 rule in 2003. Not long after that, they asked for more.

But how do you get the Government to make a change? They do it like my VC industry does it… getting our industry associations to do it for us…

Two Canadian pension associations are asking the federal government to scrap the 30% foreign content limit on registered pension plans. A study commissioned by the Association of Canadian Pension Management and the Pension Investment Association of Canada concludes that eliminating the foreign content rule could be worth as much as $3 billion a year for Canadians with company pensions or RRSPs.

And they got it, as the CPP 2005 year-end report states.

..we comply with the foreign property rule in a similar manner to many other public pension funds in Canada. In its recent budget, the federal government announced plans to eliminate the foreign property rule…

The CPP Investment Board welcomes this policy change because we believe that the broadening of available investment opportunities will benefit CPP stakeholders.

So, remember the history that I quoted earlier? It is a bit misleading and missing some context.

In 2006, CPP Investments decided to adopt an active management strategy to help improve overall returns for the CPP Fund.

The CPPIB didn’t decide to go into active management. They lobbied hard to be able to do it, culminating in the change in 2005.

You haven’t heard of this but have been a beneficiary of it. Before this, an RRSP or Pension plan was required to be 70% Canadian. Only 30% of the investments could be used for ‘foreign’ investments. Why? Well, you aren’t paying capital gain taxes, are you? Tax-exempt investments (like those investments within an RRSP) and pension plans (i.e. accounts that did not pay taxes on capital gains) don’t pay tax... if you wanted to invest more outside of Canada, you could - just not tax-free. So, Canadians welcomed the change.

The CPPIB and all Canadian Pension Plans were also beneficiaries of this change. To be clear, there were some clever ways around this (using derivatives and such), but by and large, most people accepted the 70/30 rule.

My friends at the Canso fund have a great primer on this episode.

Where did this Foreign Property Rule come from?

The foreign property rules were introduced in 1971 by TRUDEAU the 1st to ostensibly secure a domestic source of investment funding for Canadian businesses, lower the cost of capital for Canadian enterprises, and stimulate the domestic economy. The percentage was set at 90% Canadian for tax-exempt investments. As the budget said:

The legislation limits foreign inveàtments of employee pension plans, registered retirement savings plans and deferred profit-sharing plans to 10 percent of the cost of their assets. Past foreign investment limits have been based on foreign income rather than cost of foreign assets, and the limits have not applied to registered retirement savings plans. A special tax will be imposed on excess foreign investments held at the end of each month. This will be one percent of the cost of the excess investments held.

So the thinking was that Canada lost out on Taxes of these exempt entities but gained on lower Capital costs for Canadian businesses. Everyone would win, including retirees with a product outside their pensions that was incentivized for retirement.

By the 1980s, people realized the Foreign component needed to be higher. It rose to 20% in the early 1990s, 25% in 1999, and settled at 30% by 2001. This stringent component was a bone of contention: did it or did not help Canada?

The belief and the whole reason for its existence was that it would lower the cost of capital for Canadian businesses. Economists are still out on that question—what it did was increase the investment in Canadian public equities, so, by some measure, it made it cheaper to get capital on the public markets.

However, Canadian equities were widely given a “premium” relative to their foreign peers, which was detrimental to returns. There are some excellent Graduate Economics dissertations on all this if you like. But the range of that cost to Canadians was roughly between 0.2% and 1.1% annually on returns—so, in any measure, it seems it was minimally detrimental. So good for public companies and somewhat bad for the average investor.

Then, Boom, it was removed. The 2005 change was interesting in what CPPIB and their other Canadian Pension counterparts said to the Senate and House committees when they asked for a change.

Because they never asked for it. At least not publicly.

As a surprised senator inquired after its repeal:

Senator Plamondon: As a member of the Standing Senate Committee on Banking, Trade and Commerce, I can tell you that, a few years ago, the decision was made to increase the foreign investment limit from 20 percent to 30 percent, whereas now it is going from 30 percent to 100 percent.

Are there documents justifying such a change? Were any studies conducted? Will this matter be referred to the Standing Senate Committee on Banking, Trade and Commerce for its consideration? Could you table the documents justifying such a decision?

The answer was no.

Beyond some brief discussions at the House Finance Committee, there were often discussions of further reducing the Foreign Investment Limit threshold, including a private members’ bill to eliminate it outright. But it was never the main event—it was usually an aside or comment made by Pension leaders when discussing other matters at committees.

However, the legislation to eliminate it was put in the omnibus 2005 Budget. It was not an individual bill. Thus, it didn’t go through the usual channels of the parliamentary and senate banking committees to discuss the short, medium and long-term ramifications.

Surprisingly, this radical change had not been discussed, researched, or debated, except for that one private member bill.

As now retired Pension CEO who was there at the time said to this intrepid VC on a Zoom call earlier this year:

“We wanted it for sure; it never occurred to us that we would get it. At least not for a decade or so, and in fact, only a few Funds knew it was coming - we were pretty surprised until we were told before the budget planning process had been completed; until that - we had no idea. The Martin government had said they’d review it, but the change was fast. We knew this represented a huge win. But at the same time, we hadn’t really planned for it. If we had, you would have seen us holding back on other investments we’d committed to before the change.”

Reporters at the time were asking questions about impacts, and the Government hastily tried to find out what those would be after they had already announced the change (!) It is worth sharing here the highlights of the report - they are essential to why this change was allowed:

The Finance Department report, obtained under the Access to Information Act, tries to predict the impact of the Feb. 23 budget announcement that removed a 30-per-cent cap on the foreign content of pension funds. The heavily censored March 8 study says pension funds and RRSP holders are again likely to add only moderately to their foreign content, even though there's no longer any legislated ceiling.

That's partly because of an international phenomenon known as "home-country asset preference." Investors show a strong bias for stocks and bonds in their own backyard because it's often more difficult to get information about investments in a foreign country.

"The gains from a completely diversified portfolio do not compensate for the higher information costs of investing in foreign countries," says the report.

Drawing on published studies, the authors assume that Canadian pension funds will, on average, raise their foreign content to about 33 per cent from the current average of about 26 per cent.

That would mean about $67-billion will leave the country over two years as a direct result of the new policy, the study concludes.

Mr. Friesen agreed that "home-country asset preference" is likely to moderate foreign-content levels, perhaps to about 40 per cent -- as is the case in Australia, whose economy is similar to Canada's.

A spokesman for the Finance Department said domestic capital markets have matured, and the rule change won't make it more difficult for Canadian companies to raise capital.

"We don't see the removal of the FPR [foreign property rule] significantly affecting either the exchange rate or the ability of Canadian companies to access capital," David Gamble said in an interview.

“We believe that the current short, medium and long-term economic environments are supportive for eliminating the foreign property rule,” says ACPM president Keith Ambachtsheer. “We do not think there would be any material effects on the Canadian dollar, the balance of payments, job creation, the ability of Canadian governments and corporations to raise capital or the cost of capital in Canada,” he adds”

In the same article, the authors also pointed out that Norway had done this with their funds. Helpfully forgetting, the Norweigan Pension Plan is a predominantly Nordic and domestic-only investment fund. The Fund they were referring to is the Norway Petroleum fund, which is not a pension plan. This example is often used in multiple arguments within Canada, but it isn’t not a fair comparison.

Regardless, the economist's salesmanship of the benefits was focused on a no net negative for Canada thesis, but notice the important point being made: ‘no net change to the ability of “Corporations to raise capital or the cost of capital.’

The Federal government had more promising ideas outlined in its policy briefing. The CBC has kindly parsed the government Budget brief:

Eliminating the FPR has the potential to also increase the supply of venture capital (VC) from pension funds to Canadian small businesses. Since the FPR defines most limited partnerships (through which VC investments are typically made) as foreign property, some pension funds claim it acts as an impediment to VC investing. This is despite the fact that "qualified limited partnerships," the rules for which have been developed and refined over time in consultation with the pension industry specifically to facilitate VC investing, are not classified as foreign property. This budget clearly ends any remaining ambiguity.

The proposed elimination of the Foreign Property Rule (FPR) in Budget 2005 has the potential to increase pension fund investment in VC. Going forward, the Government of Canada will continue to work with the investment, venture, and angel capital communities to ensure an efficient venture capital market for early-stage small businesses in Canada.

This did not happen; as time would show, the opposite occurred.

Lies, Damned Lies & Statistics

Most of the things the government and Pension Leaders believed would happen when they eliminated the FPR were false, as time would show.

Almost immediately after the changes, in late 2005, CPP transferred all their Canadian Venture and PE Fund investments to a small fund of funds you may not have heard of. They’re well known in my industry, and they’re called Northleaf.

Northleaf Capital Partners was selected in 2005 to manage a previous $400 million commitment by CPPIB to smaller Canadian private equity firms and Canadian venture capital firms.

The mandate of this additional investment is to focus on Canadian small/mid-market buyout, venture capital and growth equity funds that are seeking to raise $750 million or less in capital commitments.

CPPIB was out of the direct investment game in Canadian Venture or PE, all within months of the change.

They weren’t alone.

OTPP (colloquially known as Teachers), who also benefited from the legislation changes, joined CPP in massively changing their Canadian Venture exposure. In the year 2000, Teachers were proudly sharing information with Pensioners on their Venture investments in Canada:

Our merchant banking portfolio includes a venture capital fund launched three years ago that ranks among the top sources of early-stage capital in Canada. Investing in start-up enterprises carries higher risks in the expectation of higher rewards. Our size, long-term investment perspective and diverse asset base allow us to take risks in the most promising opportunities on the assumption that the successes will exceed the costs of failures.

At the end of 2000, we had $329 million invested in 24 companies and 12 venture capital funds, principally in life sciences and information technology. These investments typically involve multiple rounds of financing of $3 million to $20 million each. Approximately 54 percent of our venture capital investments are in Canada and 46 percent in the United States.

What happened to those investments after 2005?

Teachers stopped reporting on their Canadian VC fund or Domestic Venture LP investments—they’d shuttered the Canadian direct investment group. But they continued to invest in their International Venture LP commitments (i.e. they invested in American Venture funds), which grew on their balance sheet without comment and continue to do so to this day.

OMERS was also an LP in Canadian VCs as late as 2004... By 2006, there was no mention of Venture investments in Canada (until 2010 and a 2021 investment in Graphite Ventures—both of which are stories for another day).

Other pension plans across Canada followed suit. This departure from the Canadian VC and PE market was widely noticed in the industry stats.

By 2007, only $1.19 billion had been raised by Canadian VC funds, and 70% of that new capital for VC funds had gone to only Quebec-based organizations.

But why was Quebec doing so well?

Because of their version of CPP, CDPQ had to invest - the plan was given a dual mandate of growing the Quebec economy and maximizing returns. But outside Quebec, the Canadian VC ecosystem was dying.

So in Quebec with CDPQ Venture Capital fundraising went up, while in all the provinces with CPP - VC fundraising collapsed. If you want to understand my previous article on the death of Canadian Venture in the 2000 to 2010 period. Here is the main suspect if we’d done a post-mortem.

How bad was it?

In 2008, Foreign VC firms represented 64% of all the Dollars in Canadian VC deals. Only 4% of Canadian Venture deals were led by independent domestic funds. Corporate or Government funds took the balance. So it wasn’t for a lack of deals. Or even good deals - Americans were coming up here all the time. There was no money from anyone outside of corporate, government, or American funds to give them cash.

To put it mildly, that constitutes a divergence from what the government said would happen for the VC industry post the regulatory changes. Remember this quote:

Eliminating the FPR has the potential to also increase the supply of venture capital (VC) from pension funds to Canadian small businesses.

Well, not so much...

The Feds believed we could see more venture investment, but we saw less. I’ll return to the venture world in a moment, but let’s look at the effects outside my world. The VC industry is not Canada’s economy, so what happened elsewhere?

In particular, what about the public markets?

As we heard in the federal policy documents, displacement was expected. But not too much. Because:

Investors show a strong bias for stocks and bonds in their own backyard because it's often more difficult to get information about investments in a foreign country.

Well, we’re still waiting for a bias toward Canada:

I guess, with hindsight, the question is, when should we expect this displacement to end? It’s been 19 years, and we’re still experiencing it.

Biased Against Your Home

In the 1990s and early 2000s, there was a thing we called the Canadian Stock Premium. There was so much domestic investment that Canadian stocks traded higher than their U.S. and International peers.

That is now long gone, and a IPO’s in Canada are rare.

Daniel Brosseau and Peter Letko led the testimony. If you don’t know them, you’re missing out. They are both powerhouse minority shareholder rights advocates and phenomenal public market investors.

They made an impassioned and direct case for the committee to review the minimum level of pension investment in Canada.

“In the old days we had appeared before the same parliamentary committee,” he said. “Forty years later we were back at it but now we are arguing the opposite.”

However, let’s parse out some points of the data they use. Most economists claim that there is bias to domestic investment-"home-country asset preference," as I mentioned earlier. This was the original case for the government not setting a minimum threshold for investment—the domestic minimum would come out in the wash of the home bias, so there is no need to set it.

Here’s a nice chart that shows it to some relative peers.

Canada continues to be at the bottom of Domestic Investment in every category.

Even though Canada makes up approximately 3 per cent of the global stock market index, large Canadian pension funds invest about 20 per cent of their listed equity portfolio in domestic firms.

First, they haven’t invested “in” the Canadian Stock market; the Pensions have been ‘divesting from’ our stock markets. They’re net sellers.

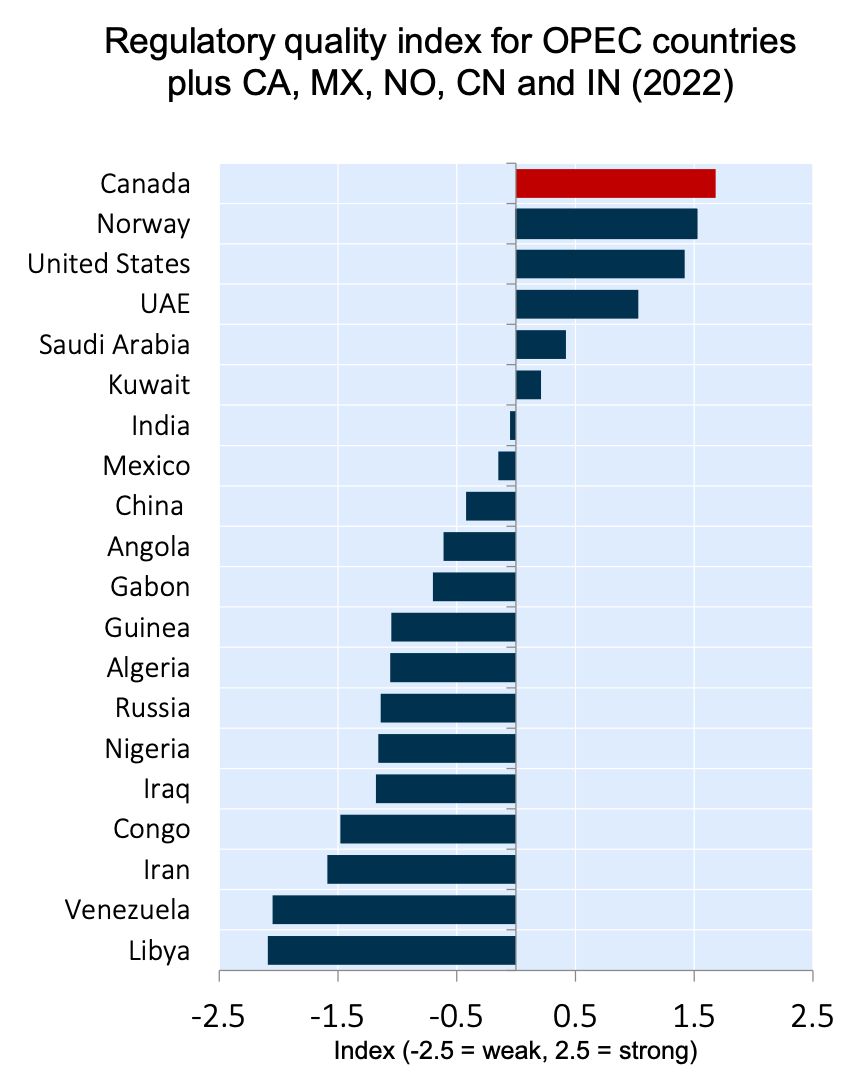

Secondly, this 3% argument is bogus, and let me head it off at the pass. The number includes places you know we won’t invest in, like Russia or Iran; dozens of other countries are on that list.

Also, other places are, you know, less great for investments because they don’t enforce their laws the same way as we do here:

There are also places where the CPP and other pensions' forget' their ESG and DEI goals, which is strange. Should China, whose human rights abuses were condemned by our government, be excluded? How about when they take two CPP contributors hostage?

I like this chart, so let me use it again. It shows that Pensions have slowly, and sometimes quickly, exited the Canadian stock market for over 20 years. They started selling back when the industry first announced the policy of removing the foreign minimum investment number; back then, the number was 75%-ish, and they said:

Mr. Friesen agreed that "home-country asset preference" is likely to moderate foreign-content levels, perhaps to about 40 per cent -- as is the case in Australia, whose economy is similar to Canada's.

That's not 40% for just Canada - that is 40% for the world… So they thought we could see the Canadian number at around 60%. Now they claim that while we're at the current level of 20%, it could be lower, maybe closer to 3%. We're just lucky it isn't.

The pension industry's "home bias" argument keeps changing - downwards - it is a declining number. We should discuss where that number is going before we hit that 3%, which, as I showed, isn't a reasonable number anyway.

So, our domestic home country asset preference doesn't exist for Canadian pension leaders, or at least, it's getting lower yearly. Our unique case shows economists that their long-held (at least 50 years) theory might not really be true.

The other promise we were told was that reducing the limit would not negatively impact the cost of raising capital in Canada. For reference:

"We don't see the removal of the FPR [foreign property rule] significantly affecting either the exchange rate or the ability of Canadian companies to access capital," David Gamble said in an interview.

It did, which is self-serving because no venture capital is, of course, costly to future businesses trying to raise capital, but are there any other examples?

Well, we're now seeing that every time Canadians pay more towards their pension - they save less - because why should they.. they've got someone else putting that money to work for them, and taxpayers have less to save as they're poorer (remember, taxes are theft). That money is gone in a tax - yes, it gives them pensions, but it’s not widely thought of that way until you get the pension. So, as this Fraser report points out, thanks to a new CPP contribution we started this year, less money is likely to be invested in Canada because of it; how much less? Well…

2030 Canadian household assets invested in the domestic market would be approximately $11.8 billion lower.

In short, CPP pension contributions make it harder to find investment in Canada, which is common sense, but that was not what we expected. At least, that’s not what we were told or believed would happen back in 2005.

Getting Back to Venture

When in 2013, I attended the Canadian Venture Capital Association annual get-together. The CPP CEO was on stage talking about their strong support for Canadian VCs. I sat in a back row with some very surly GPs, one commented on the presentation:

“What fucking support? And who invited him?”

CPP's CEO at the time, Mark Wiseman, claimed on stage that $2.4B was invested in Canadian Venture and Private Equity through their Northleaf relationship. The number was probably an actual, but that included over 15 prior years of investments.

Today, eleven years later, with CPP having 2.5 times the amount of assets under management, how much has CPP invested in Canada through that relationship? (as of November 2023)

CPP Investments has committed C$200 million to the Canadian private equity market through an evergreen Canadian mid-market mandate managed by Northleaf. Since the partnership was established in 2006, and with this allocation, Northleaf now manages a total of C$2.4 billion in Canadian private equity investments on behalf of CPP Investments.

It’s the same number!

Or less if you take inflation into account.

You might think that this is because Canada is a horrible venture market to invest in, but that's unless you no longer work for CPP, in which case Canada is the place to be!

Like that time, the former head of CPP resigned and then started a Venture fund focusing on Canada!

“You have this extraordinary ecosystem” in Canada, said Mr. Machin, Intrepid’s managing partner. “The thing that I heard many, many times when I was in Canada, and it’s also to some extent the case in Europe, is the lack of growth capital, lack of scale-up capital. And so that’s where we think there continues to be a really interesting opportunity to help Canadian companies grow and thrive.”

Sometimes, you can’t make this stuff up.

In fairness, CPP has made one Canadian LP investment backing Radical Ventures and one direct investment in Deepgenomics. Both are stellar from this seat, and that's the first time we've seen them as a direct LP or venture-like investor in nearly 20 years. (There may be other VC-ish investments or LP commits, but I have nothing.) But FYI, this was all coincidentally done under the aforementioned former CEO, who left in 2021.

However, the recent tepid support for their crucial local fund of funds partner, their massive selloff of equities within Canada, and their complete lack of any team members focused on domestic investment leads me to believe these were one-offs. Ask a Canadian GP Fund manager who they would call at CPP to share their investment pipeline, and you’ll often get a shrugged shoulder. At best, Canadian VCs get access through their Northleaf relationship.

So, how does CPP find their Canadian deals (or that 1 deal)?

Through their American GP's. That's how they found Deepgenomics, from True Ventures, a seed-round Deepgenomics investor with CPP as an LP.

So, if you want the Canadian Pension Plan to invest directly in a Canadian tech startup, you will need to do so through a venture fund it has previously invested in. Today, that means a US-based fund because they don't invest directly in VC funds here.

But back in 2005, you'd find CPP backing Canadian GPs with $50M cheques while talking about building the VC Fund Management community. I was a young Analyst whose firm co-invested with them in that fund. Today, CPP politely asks you to call the fund of funds to which they've outsourced the job, Northleaf, with whom they've given an inflation-adjusted smaller amount of money to do that job over the past 19 years.

As I've shown, this was not the deal we were told to expect when the Foreign restrictions were removed from our pension plans. Since its removal, the entire tech ecosystem in Canada has become more government-dependent. VCAP/VCCI was an attempt to turn around this lack of LP investment created by the absence of our pension funds, but more is needed. And it still doesn't solve the private/public dilemma.

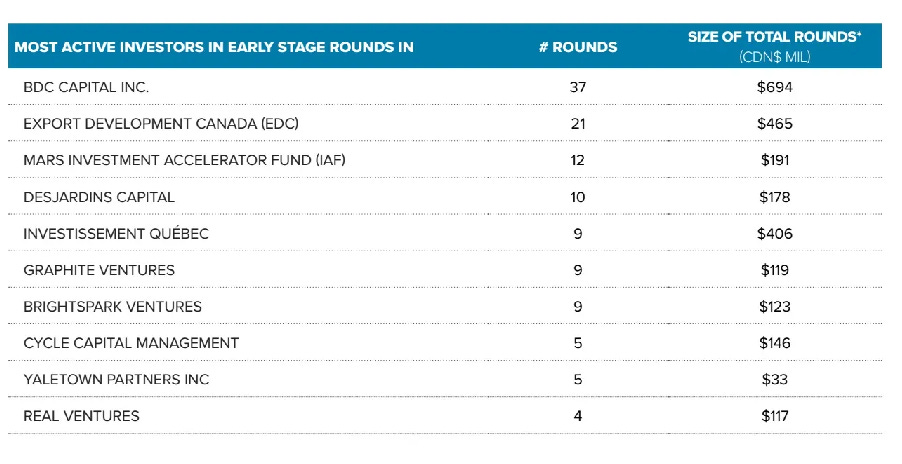

If you look at the list of most active funds for FY2023, it's a who's who of government funds.

Or most active at the early stage

But honestly - nobody cares, it seems. This has been the case for over 15 years. It is not news.

So why now?

So, why is everyone talking about Pensions now?

Two reasons.

First, take a look at your Pay stub. There is now a new CPP contribution if you're in a particular tax bracket. This enhanced CPP, of course, means larger contributions from businesses.

Those businesses have leaders who are beginning to wonder why they shoulder a new tax (for them, that is all it is) considering how little it benefits their companies or Canada.

That letter released earlier this month was a virtual who's who of our business leaders. They all see more payments and know explicitly that the pension plans are not helping with their cost of capital. So, in that context, they also view CPP contributions as an unfair business tax.

And now you might have some sympathy for Premiere Smith in Alberta. Because CPP is committed to not investing there, CPP's:

Commitment is a continuation of the organization’s long and successful track record of integrating ESG considerations, including climate change, into investment activities.

It's not explicit, but the undertone for a resource economy certainly feels that way. You might agree with the CPP's view. Still, wherever you stand politically, you can understand why local Albertans might question the CPP benefit for local businesses that employ them - beyond a pension plan. And this is, of course, the heartland of Conservative voters.

When the Martin government eliminated the foreign investment rule in 2005, it came less than a year after a Conservative MP sponsored a private members bill to eliminate it. So, the opposition conservatives broadly supported the change in the 2005 budget. Today, Pension CEOs cannot expect unfettered support from them. They view much of the DEI and ESG rhetoric coming out of Canada's pensions as both detrimental to Canada's economic interests and a signal that leadership isn't focused on 'best' returns but on the culture wars, of which they're on the wrong side and only playing them in Canada.

The current leaders of the Red (liberal) team are learning that the pensions leaders are not sticking to the bargain as they understood it 20 years ago. Particularly on a key plank of their economic agenda, The Canada Infrastructure Bank is seemingly flailing:

The Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB), a federal government financial institution, opened its doors five years ago with great promise, vowing to deploy $35 billion of investments towards “the next generation of infrastructure Canadians need.”

But rather than investing public money in public services, the CIB has instead privatized our water, transportation and electricity. For every dollar invested by the CIB, the hope was that $4 to $5 would be invested by the private sector.

Five years later, the CIB has not been able to deliver on its promise. Of the $19.4 billion invested to date, only about one-third has come from private and institutional investors ($7.2 billion).

So, strong support in Ottawa is not guaranteed.

Also, support is also mixed within provincial capitals outside of Alberta.

Mr. Bethlenfalvy, Ontario’s Finance Minister, said “we agree that Canadian pension funds should invest more at home,” in an e-mailed statement

This is important because provincial governments matter as much as their federal leaders when it comes to changing the CPP—so while the legislation for those tax-exempt entities comes from Ottawa, the provinces and feds are equal partners. If Alberta gets a decent ruling on leaving the CPP in the fall, they might be offered some serious changes to the CPP's rules to keep them in the program.

Second, you might think, '"This is all self-serving for Matt and other Canada-based investors; they want that pension money."

That’s what Pundits are saying. Chastising business leaders who are seemingly asking for a handout. Businesses,

think it’s the government’s job to keep their revenue streams flowing like the spring ice melt. Some 90 of them — bankers, auto executives, airline bosses, telecom chiefs — fired off a letter to Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland this month pressing her to “amend the rules governing pension funds to encourage them to invest in Canada.”

Business Leaders asking the government to use their tax contributions to reinvest in their industry is hardly a subsidy… Remember, business contributions pay for half the CPP. So, by extension, Canadian Businesses subsidize the CPP, which takes those dollars and then invests in their competition abroad.

Regardless, I would undoubtedly like lots of that sweet, sweet Pension money to flow my way. There is more of a fundamental reason we should revisit our pension’s geography focus.

You may have heard that ‘Canada is broken’ recently, But why?

You can see the cause with this nifty chart.

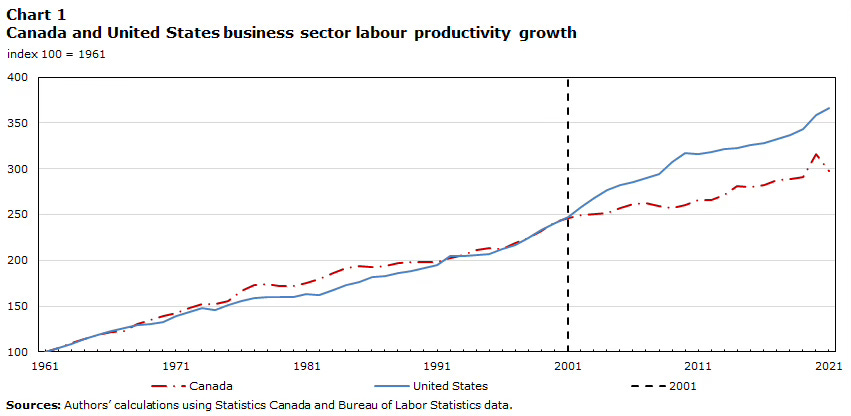

Canada’s productivity has been a disaster for most of my adult life. It predates Facebook and Twitter (X), so we can’t blame social media for this. It’s not just horrible in comparison to our southern cousins but comparable to everyone in the OECD. People online harp on per-capita productivity but thats’s not where economists see the problem. The divergence is dramatic starting in 2001. So why is it happening?

The problem is not that we have too much labour, but too little capital – machinery and equipment – for labour to work with. As a recent study for the C.D. Howe Institute has shown, the alarming deterioration in our already poor productivity performance closely tracks the extraordinary collapse in business investment in Canada in recent years – to levels that are not only lower than in other countries (the study estimates new capital per worker in Canada at less than $15,000 in 2022, compared to $20,000 in other OECD countries and almost $28,000 in the United States), but lower than the amount required to replace existing capital as it wears out or grows obsolete.

A country with one of the world's largest and best-funded pensions has businesses starved of capital to drive productivity growth. And this seems to have occurred simultaneously as premiums increased and those pensions stopped investing in the country. You can see that more clearly in this nifty chart. Remember, in the early 2000s and the late 1990s, the ratio changed from 80/20 to 70/30 and ultimately to no limit in 2005.

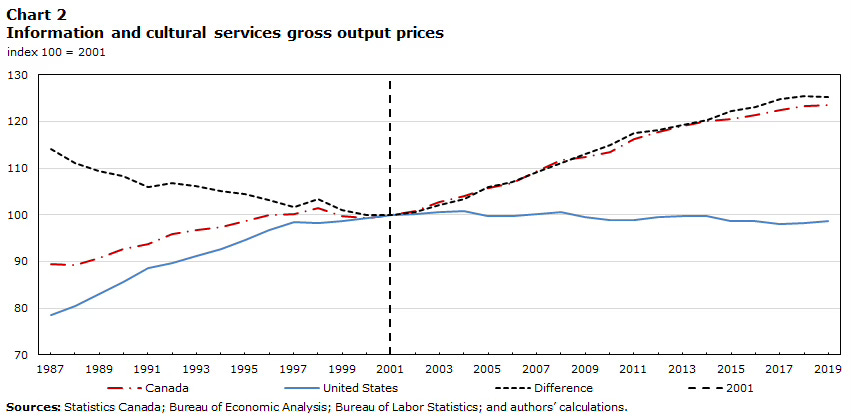

From 1987 to 2001, the information sector’s output price grew slower in Canada (0.79% annually) than in the United States (1.75%). However, from 2001 to 2019, Canada’s output price accelerated to 1.18% annually, while the U.S. price declined by 0.07% annually, contrasting with trends in the broader business sector.

In Canada, TFP growth improved, but by one-sixth the rate of the United States. By contrast to the United States, capital intensity growth fell in the information and cultural services industry in Canada, resulting in a weakening of labour productivity growth.

The authors look around and blame trade and regulatory restrictions for this dramatic difference. However, what they forgot was that the cost of the CPP contribution increased. The CPP premium changed—they essentially doubled from 1997 to 1998—while access to capital declined as the investment focus of our pension funds changed. It was a double whammy.

Don't get me wrong—we have a mediocre regulatory environment, oligopolies, and protected sectors of our economy. I'd say that increased competition in Canada, which would force a sea change in productivity, is not on the agenda in our political discussions.

However, we had many of those same structural issues in the past. Productivity growth was not great, but better in the 1980s and 90s. We also had pension plans that invested in Canada, while CPP contributions from businesses were lower.

Productivity Growth makes us all richer. And it is driven by investment. New companies (i.e. VC-backed ones ) are one component of that, but so is making it easier for existing and established companies to get investment—and if you can't raise money on the public markets or easily get private equity money in Canada, your only recourse is our Banks.

Let me repeat: CPP is 50% driven by business contributions. For every $1 from a contributor like me or you, a business matches it. You can't help but notice that the missing money from Canadian businesses’ investment in productivity correlates nicely with the money they pay into CPP.

So every time someone says that businesses are asking for a subsidy when they want the CPP to invest here, remember that the CPP's money comes from those same businesses. They're the contributors who have no voice—now they're asking for the government to review a decision that has proven detrimental to both them and Canada. I might add that this decision had numerous effects our political leaders did not expect.

How do we get that money focused on helping with productivity?

“You’ve got to create the opportunities,” said Jim Leech, former CEO of Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, which now manages $250-billion. “It isn’t forcing or enticing people into Canadian investments, it’s providing sufficient good investments in Canada.”

We have a chicken and egg problem with our pension leaders and domestic businesses.

Businesses are asking for investment to improve productivity, which is good for Canada. They also contribute to a large local pool of capital, but that fund is seemingly exiting the domestic market. So businesses are asking why they're funding a pool of capital that never invests here but often in their foreign competitors. The world turns…

That has been the life of Canadian Venture for the past 15 years. Now our other businesses are feeling it.

But this is not going to be solved by someone in any of those groups.

It requires Political leadership.

The difficulty in accessing capital in Canada exacerbates this issue. Meanwhile, these same Canadians have a significant investment in pensions funded by the government, taxpayers, and these low-productivity businesses.

You’ll hear CPP leaders and their supporters claim they are simply following their mandate to 'maximize returns, without undue loss.' This is true, and that language has been in their mandate since CPPIB was created in 1997. It was there when they were forced to invest in Canada to the tune of 80% and 70%. And when the rate was eliminated, their returns did improve. But at the expense of Canada’s productivity growth and capital availability for businesses. So, it’s time for CPPIB, as well as other pensions and those they answer to, to find a way to invest in the best of what Canada offers and build the next generation of Canada’s businesses.

Lots here for policy makers to chew on

Great read Matt!