MSBi - Canada's most important Venture Fund

Part 3: 2002-2008 - The fund you've never heard of but already know.

A Conversation at StartupFest 2024

At 8:30 a.m. on a hot July day at StartupFest 2024, over 25 emerging managers from across Canada met in a small room designed to accommodate less than a dozen people. All seats were taken, and with standing room only - they'd gathered to hear some wisdom from Canada's most successful emerging manager, but one from the previous generation. Chris Arsenault, General Partner of iNovia, led a roundtable discussion to answer questions about his perspective on Canada's venture and LP markets.

He was uniquely situated to discuss this topic.

iNovia managed a Seed and Series A fund and raised its third Growth Fund a year earlier. Their AUM was in the Billions, and with offices in California, Toronto, Montreal, Waterloo, Calgary, and London, England (not that fake one in Ontario). iNovia was and is a truly international brand.

Chris politely and deftly answered all the questions from every manager. This allowed them to ask follow-up questions for clarity, but one question caught this observer's attention.

"How long did it take you to raise iNovia's fund?" asked a smart, newly minted GP on her first fundraising journey.

"You know, it wasn't short. It took approximately two years from the start to our first close. It was challenging, and we weren't sure if we could complete it. You've got to have perseverance and some luck to get this done." Chris smiled, "and you have to have an understanding spouse."

Later, Chris and I walked from the event to a quiet corner at StartupFest to catch up over coffee. And I pointed out his answer to this specific question.

"So, you know,” I said, “that wasn't exactly the truth. I remember it being a bit more complicated back then."

Chris looked me in the eye.

"It wasn't a lie either," he said with that patented Chris Arsenault smile. "If I had told the whole story, I wouldn't have had my time for coffee with you. Plus, if you think it’s so interesting, I'll let you tell that story."

And then I realized I had a task in front of me.

The Aftermath of the Brunet Report

That is why I'm now on my third and final post about the Venture Capital market in Quebec.

In my last post, I discussed the lead-up to the Brunet report and how that report set up the Venture Capital structure of the Quebec tech Market as we know it today. Well-intended and ultimately correct in many ways, it led to the demise of locally based early-stage venture firms and the destruction of local institutional venture experience.

A TL;DR of that section of the report called for traditional limited partners (LPs) to exit the seed market, allowing private funds to flourish, and for the government, as an LP, to help fill the early-stage gap. The Government dithered, and as a result, seed funding collapsed.

A helpful English translation of the report’s key point.

"The government should withdraw from certain phases of funding directly, but it is unlikely that private venture capital firms will agree to cover the seed and startup phases, which are very risky."

Thus, the government program initiated to fill that early-stage LP spot in the market led to an unlikely alliance between BDC and the Quebec government, establishing BDC’s largest seed fund, Go Capital.

That fund intended to address the issue that no seed funds were available for the LPs to invest in after they had spent five years without investing in Seed funds. Effectively, they had waited too long, and many experienced early-stage VCs had left the market. One might say the government created a problem and solved it by doing what they had set out to avoid in the first place. 2002-2007 in Quebec—The Seed market in Quebec was effectively frozen.

How frozen, as per CVCA (2007):

Venture capital investment in emerging Canadian technology companies continued to decline in Q3 2006, to $331 million, a 32% drop from the $489 million invested in Q2 2006.

Investment patterns through 2006 continue to show a shift away from new companies, as more than 85% of all capital deployed in Q3 2006 went to follow-on investments in existing portfolios, and two-thirds of all investment was classified as later-stage.

Using back-of-the-envelope math, these numbers translated into less than $50 million of new VC investment in Canada during the Q3-2006 period, including Seed and Series A. What were the VCs saying?As a young(er), Rick Nathan said:

“There’s no shortage of opportunities; there’s no shortage of entrepreneurs with great ideas and strong early-stage technology companies,” he says. “What’s happening is that there is a lack of capital here. The U.S. venture funds are viewing it as a market with very little competition for them to come in and find good early-stage companies. Their overall market share has been growing significantly in the last year and a half.”

However, inside Quebec, the market withered and effectively died (as well as in the rest of Canada).

Except for in one spot...

Valorization or Valorisation?

One spot the Brunet report had called out specifically was to:

"Encourage universities to place greater importance on commercializing public research and developing spin-off companies."

You’ll notice that this is what governments and pundits call for during every tech downturn.

But why did the report call for this?

Quebec funded extensive research at universities and public institutions, and I mean extensive.

Let's talk about R&D spend. This is a chart of the provincial government’s R&D spending, Quebec vs. Ontario, 1990– 2003 ($ millions), which includes government labs, universities, research institutes, etc.

This chart doesn't include private sector R&D, which would have distorted the numbers. However, Quebec believed that it had invested significant money in R&D and hadn't seen many outcomes beyond successes in Biotech. Even there, it hadn't seen as many as it had hoped.

We referred to this type of work as 'tech transfer' back in the day, and if you're of a certain age, you likely have strong opinions on it. Here's a quick fake example for readers less familiar with this subculture.

A brilliant scientist and their Master’s students worked hard for years on an arcane point of technology; for example, let's say it was some digital voice compression technology, and once it was working, they needed to develop it into a product.

But they're scientists, so a person with a business background joins up. The university, which owns the IP/Patent and houses the team, spins it into a company.

The scientists go along for the ride and then raise venture capital dollars. Commercialization and sales occur, and success ensues.

If this had worked as intended in Quebec, political leaders believe the province would be awash in great deep tech companies—except it wasn't. To illustrate how poorly it was working, Quebec probably had the most significant 'miss' on the tech transfer front in history—or did they?

Remember that example of voice compression technology from before? Surprise! It's a true story...

Except (perhaps sadly) for the whole Venture Capital part...

In a story you have never heard of – because you don’t speak French or are young - The University of Sherbrooke (Canada’s most underrated University tech hub) made more licensing revenue in the 1990s/Early 2000s from a tech transfer success than any university in Canada (eat that Waterloo).

ACELP, which stands for “Algebraic Code-Excited Linear Prediction,” is used every day in more than 95% of the world’s cell phones, which accounts for more than 6 billion users.

Thanks to the partnerships the institution established with VoiceAge, Sipro Lab Telecom, and a number of telecommunications titans in Europe, Asia, and North America, ACELP technology has generated $225M in revenue for the Université de Sherbrooke and its researchers-inventors, in the form of research funding, royalties, and dividends

You can read about the 20th anniversary of this fantastic story in French at this link.

ACELP is the tech, but Voiceflow was the name of the spinout. This technology is present in every GSM phone and remains part of subsequent upgrades, such as VoLTE/5G. Every person in the world with a mobile phone uses this tech,

And to give some credit to a story that deserves a post of its own, here is a picture of all the founders. I'll point out Sylvain Desjardins, who was the president and is third from the right (and the only person I've met and discussed this with).

It’s a critical Canadian story about the potential of university tech commercialization, particularly in Quebec, that the University of Sherbrooke has named its Innovation Park “Parc Innovation-ACELP.” This would be a horrible name in any other circumstance, but why not? ACLEP paid for it!

It is Canada's most successful university tech transfer program, outside of biotech. It was listed among the world's top ten when I attended a government hearing on tech transfer. (as one does)

So that's a success, right?

Well no. Not if you're doing that whole Quebec nationalist economic thing we discussed in Part One...

In 1999, the Quebec government believed that a truly homegrown company in Quebec should have been built using the ACELP technology, creating the knock-on technologies, rather than an international group outside of Quebec, such as Nokia, Ericsson, or Motorola, which licensed it to build GSM phones. With its R&D labs in Ontario, Nortel got access with little to no local benefits in their minds.1

Why this did not happen was, in their minds, easy to see. True or not, the government of Quebec believed that a lack of local innovation capital hamstrung ACELP's technology. But what about all those seed funds from the 1990s I discussed in my previous posts? In their minds, they weren't focused correctly; they wanted tech already on the market, and now was the time to change that.

Today, these are deep-tech technologies, as they are deep in technology and less so in aspects like product-market fit or customer acquisition. Back then, marketing was not as prevalent in Venture as it is today.

There was a local Quebec (and to some extent, national) belief that other technology gems, such as ACELP, were hidden away in Quebec research institutes and doing nothing for anyone. This was true not just for "tech " but also for Biotech, materials science, etc. So in 1999, at the height of the first Quebec VC Boom, the province announced an investment in a “non-profit initiative”: Valorisztion-Recherche Québec.

Let's translate the words for my non-French-speaking friends. Recherche would be Research. Quebec is self-explanatory, but Valorisation has a particular meaning in French and differs in English.

If you are a native English speaker, you'll only bump into the word Valorization (with a Z) from Marxian economics. And if you spent some time studying Marx like me, it has 'connotations.' However, in the decades since, in Europe, particularly in France, the word "Valorisation" (with an S) has come to mean something entirely different.

For example, the EU describes it as:

The European Union's (EU) valorisation policy aims to increase the societal impact of research and innovation (R&I) investments. The policy's goals include creating social and economic value from knowledge, addressing societal challenges, driving green and digital transitions, accelerating the uptake of research and innovation (R&I) results, and realizing the full potential of R&I investments.

Which is a lot...

However, you could loosely describe valorization as an attempt to increase value through governmental action, utilizing government capital and/or resources, and leveraging influence.

There isn’t a clear word in English that means the same thing. We might use 'subsidize,' but that would not be the same. It means utilizing government funds and resources (such as legislation, subsidies, or cash) to capture or extract the existing value in something that has not or cannot be crystallized without the involvement of a government actor. (Probably the best examples we've seen of this are in clean tech and the influence of Carbon taxation.)

In other words, instead of Adam Smith's invisible hand, this is the visible hand of government, subsidizing or incentivizing all firms to act in specific ways.

It is a (perhaps subtle or not) difference, but I’ve always thought that this subtlety explains how our Quebec-based colleagues view the role of government in tech—and in economic involvement in general—differently from those of us in English-speaking Canada.

When you hear a direct translation of the word in Parliament, it's almost always subbed in for government subsidy or incentivization, which is not quite the same thing and is misleading (as to intent, if not action). (At least) That's not what they're thinking, even if that's what we in the rest of Canada think it looks like.

Regardless, the Quebec Valorisation fund had an expansive mandate. But in the interest of time, I can translate and truncate it for you.

The government thought $100M ought to be enough to find the next one to ten phenomenal technologies like ACELP, which was the thesis for a valorisation fund. It would let them build the next generation of Tech successes.

They created several initiatives and companies to help spin out technologies from universities. Most importantly, they created four companies to spin out technology from universities: Univalor, Sovar, and Gestion Valeo.

These offices and teams helped spin out and grow companies by utilizing IP developed through university research. They would interact with the existing external Seed funds and secure funding for them. Each group had different University backers and focuses.

McGill, Sherbrooke and Bishops...

But three particular schools wanted something different. They already had strong technology transfer offices and teams to help spin out companies and had successfully spun out biotech companies. What they needed was a magic power called Capital.

“There's a tremendous pool of researchers who are starving for the necessary funding to bring their intellectual property into the marketplace.” …” a catalyst that will give academic ideas a fiscal shot at commercialization”

Said, Jan Peeters, CEO of Olameter Inc., was also a member of McGill's Board of Governors.

McGill, Sherbrooke, and Bishop’s University's MSB (along with their associated hospital research institutes) wanted a venture fund. The government obliged—MSBi Capital ("i" for Innovations) was born with contributions of $11M from the universities and $15M from the aforementioned Valorisation fund.

The fund’s backers hired Mark de Groot, a Canadian physicist and businessman, as CEO of MSBi. He joined the fund after developing his expertise in research-based companies, having cofounded University Medical Discoveries in Toronto. (Subsequently, the firm became MDS Capital.) At the outset, he said precisely what he thought his job was, to create the next ACELP:

"As president of MSBi, I look forward to helping translate innovative research into successful companies," says De Groot. "MSBi will provide another opportunity for its partners to demonstrate that investing in research is advantageous to society and that research spin-offs can be an engine for economic growth."

Fun fact: If you are of a particular vintage, MDS Capital is the first truly huge biotech fund to come out of Canada. Today, the fund is one of a handful of Canadian Venture funds that have survived for over 35 years—they're called Lumira. You can follow their other cofounder and Managing Partner, Peter van der Velden. He posts about pension plans like I did. I think I inspired him.

Mark's first task was to build a team, and his first hire was a name that, today, most venture capitalists from Quebec and possibly Canada now know: Chris Arsenault. But he was not unknown in 2002. As Mark said in the announcement of hiring Chris -

“That someone with Chris’ experience in establishing, operating and investing in successful technology companies over the course of more than 10 years is joining MSBI, is a testament to MSBI’s intention to provide both financing and real management support to our investee companies.”

Some of the Montreal lore I hear today is that Chris didn't have a strong tech or venture background before he joined MSBi. This is hilarious (and wrong) because he arguably had one of the best backgrounds. Maybe people would say this now, in 2025, because they don't recognize the names on his resume, and he doesn't advertise them. However, in 2002, Chris was very experienced and well-connected.

Chris had been, before joining MSBi, a partner at a corporate venture capital firm and an entrepreneur in residence with the Telesystem group. He managed their public and private direct investments, including Popcast Communications Corp, Look Communications, and Airborne Entertainment. Airborne was the deal that gave Chris his Canadian VC Street Cred; he led the seed, followed up with A, and exited for $100M - and won the 2005 CVCA Deal of the Year award for that work. As an EIR, he was involved in launching up2 Technologies – a subsidiary of Teleglobe Inc., which was later acquired by Bell Canada - and created a subsidiary for Microcell Telecommunications, i5 Corp, which was acquired by Rogers Wireless in 2005. Along with all this, he also helped launch a $30 Million Seed Fund out of Teleglobe during this period. ](https://enablis.org/our-background)

He was a founding team member of Wanted Technologies, a business intelligence information and technology provider. He was an early employee in the launch of Copernic Technologies, one of the Quebec Dot-Com darlings of the mid-90s, but it continued to thrive in the dot-com bust. He was also an ex-founder of SIT Inc., an international Internet integrator, and the first Netscape Communications software developer, which was eventually sold to Ubizen in Belgium in 1999 for €42 million, by then, as Chris had left.

Mark, along with Chris, was a team builder. Together, they filled out the gaps in the MSBI team's backgrounds and experience. They had an expansive investment thesis, backing startups from McGill, Sherbrooke, and Bishop’s, encompassing biotech and medtech, Semiconductors, web, and materials sciences. They need people with experience in those.

Cedric Bisson, the former head of McKinsey’s Canadian Healthcare and Innovation practice, joined to round out the leadership. He was a pioneer in healthcare IT innovation in Canada. They hired Joško Bobanović and Bernie Li as associates to cover clean tech and software, respectively. Today, all three are still in the industry, with Cedric at Teralys, Josko in Paris at Soffinova, and Bernie running Antlers Canadian Operations from Toronto.

Initially, the portfolio plan was to invest in approximately 50 startups in software, semiconductor, biotech, and materials science technologies. However, in VC, with a dying market by 2002, it was clear that a volume investment strategy would not provide enough backing to companies. So, the team developed a thesis of being more selective, focusing on just a few firms and ultimately investing in only a little over a dozen spinouts.

This selectivity led to a stronger thesis for each investment, which bred a level of focus. How was success measured? By 3rd party co-investment and follow-on capital. Essentially, the problem of Quebec not finding out-of-province follow-on or co-investors was being solved by these tech transfer investors.

However, MSBi was the ugly stepchild in the Quebec Venture market during this period.

I specifically remember mentioning that I would be visiting their Montreal office and being informed by a seasoned Montreal venture capitalist that they weren't "real VCS"—and having been established and started by the at the time (2004) out-of-power PQ government, and being "pre-" the Brunet report, they were often dismissed. People believed that future follow-up funding was highly unlikely for the team.

However, that VC was not reading the right tea leaves. In the year following the release of the Brunet Report in 2004/5, MSBi raised an additional $20 million for the fund, with $10 million contributed by Solidarity Fund QFL (FTQ) and $10 million by Desjardins.

This was perhaps because of three reasons.

First, both Desjardin and FTQ must invest in Quebec regularly each year. As part of their mandates, they’ve been granted certain tax advantages in return for their promise to support Quebec's economic development within the province. As I mentioned, this was a nuclear winter for funds being raised; MSBi had funding and was continuing to deploy. They weren’t going anywhere.

Secondly, because of this, FTQ & Desjardin couldn’t invest in Funds domiciled outside the province, which other traditional Quebec LPs were doing during this timeframe.

Lastly, when I asked some people who ran these investment groups what they were thinking at the time, with the benefit of hindsight, they gave me a name. Chris Arsenault. As mentioned, he was highly regarded within the ecosystem. Chris had credibility from his time at Telesystems, whose CEO, Charles Sirois, was a huge supporter. Today, when you ask a retired FTQ LP why they invested, the exact comment I got (in my badly mangled French translation, “Chris made it an easy decision, Charles made it an easy discussion with my bosses (at the investment committee.)”

Bringing in their first true institutional investors allowed MSBi to invest beyond traditional University spinouts if they wanted to. They now had a small fund to work with.

Tough times in the early stage

As I discussed, 2005/7 was a 'nuclear winter' for seed investors in Quebec. While the Quebec government delayed its announcement of a large fund of funds, it also postponed meeting its Brunet recommendations to support the Seed market separately. The complaint was that they wanted the Funds to be very close to their closing before their institutional capital would jump in, and a chicken-or-egg problem began to become apparent. MSBi was experiencing the same issue. I love this quote from a team member. And if you remember, I used it at the beginning of Part One:

“In 2007, I took a leap of faith and joined a small venture capital fund called MSBi Management, which, back then, invested in life sciences and semiconductors. And when I say a leap of faith, I’m not kidding. The team was preparing to raise a second fund, and if it didn’t work out, they would not be able to afford to keep me on the payroll. It was that simple."

That quote is from a now-retired Francois Gauvin. He was alluding to how he was convinced to join MSBi , a small fund that was struggling to close a new one.

Francois did take a leap of faith. He left one of those jobs you don't quit: he was at Quebec's FSTQ. A fund manager with billions under management…

So why the leap of faith?

Why would he join any Quebec venture fund at such a crappy time? As I just mentioned, no seed funds were getting funded.

What made MSBi different?

Magic. Or that they had an anchor cheque for their next fund.

What is an anchor cheque?

An anchor cheque is a financial commitment, usually (but not exclusively) from an institution, that provides more than 20-25% or more of a fund's total dollar commitment. Anchor cheques are rare and often come with strings attached. Today, in Canada, they are virtually unheard of.

When I was a Partner at ScaleUP Ventures, we had one from the Ontario Government. However, that was in 2016, ten years earlier, in 2006, when MSBi was raising money; it was the worst period ever for Canadian venture capital fundraising.

But MSBi had a gateway commitment—an anchor with no other obligations except matching commitments.

Where did this cheque come from? Well, in 2005...

A blockbuster announcement came down from the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) that it would implement a whopping $100-million fund to seed early-stage companies.

...

BDC's Elder, whose phone is already "ringing off the hook," is clearly excited by the prospect of his organization leading the charge into what could be a billion-dollar renaissance of early-stage funding in Canada. While policy analysts have estimated the "funding gap" to be as high as $5-billion, the BDC's move is definitely a leap in the right direction.

"In the past, with smaller funds, it has taken up to 18 months, or even longer, to attract matching funds, creating a huge opportunity cost for the earmarked funds," points out Mr. Elder.2

This was a key change from Canada’s Development Bank (BDC).

The article misunderstood what Brian was discussing. But if you know our (VC) lingo, it stated BDC would anchor 3-5 early-stage, regionally focused funds to get them started, as long as they found matching leverage. The "Mr. Eder" in the article is Brian Elder, who managed the fund of funds group at BDC during the 2000s, a thankless task then as it is now. Brian, who has long since retired from BDC, was iNovia's first and only signed commitment throughout 2006.

I had to call Chris and ask him about this. Didn't the term sheet have an expiration date?

"If it did, I didn't mention it to anyone," he recalled.

Fundraising Moneyball

Loosely speaking, the book Moneyball describes how the Oakland Athletics built a competitive team on a limited budget by identifying the statistical attributes of players to create a winning team. What is a winning team? On base percentages, the more on base a player is, the more 'in the game' they are - i.e., they are likely to win.

In Venture Capital, you need a fund to be in the game, and you require two key elements to achieve this: a team with the right attributes, your potential LPs' prioritize, and the inevitability of fundraising momentum.

Chris used that BDC anchor cheque to play what I call Canadian Fundraising Moneyball, and in fairness, I think Chris Arsenault hates the term - but hear me out.

Chris would describe himself as "a smart GP team builder" or GM - but that’s him looking back. He built the winning team for fundraising and deployment, and he used his anchor cheque to build momentum and win the fundraising game gradually and then quickly. At the time, and with hindsight, it was a masterful lesson in VC leadership.

As I mentioned, Chris convinced Francois Gauvin to come aboard as CFO of MSBi from Quebec's FSTQ. As we've seen in the previous discussions on the Quebec ecosystem, institutional trust came from knowing that it had strong linkages back into the local financial ecosystem. And François was easily that, but not only was he a financially experienced individual; he was also the Investment Director at the Fonds de solidarité FTQ, where he was responsible for many investments in venture capital funds. Having someone with deep experience as a leader or professional from an LP join your team is never a bad move.

Chris wanted MSBi to bring in people with US networks and experience. At hand, he found John Elton, who had also been working with the McGill tech transfer office. He joined from Turnstone Capital and had been at Gulf International Bank (UK), 24/7 Real Media, and VSS (Veronis Suhler Stevenson).

While Alberta-based, Shawn Abbott joined the company later that same year, in 2007.

Shawn was (and still is) well known for inventing the standard for plugging in USB keys into your PC, and it works as if by magic (his name is on one of the patents). However, he was better positioned in this context as one of the presidents at Rainbow Software, which grew through acquisitions during the dot-com collapse in the security software space. I first met him just after he acquired Chrysalis Software, a company based in Ottawa. Shawn’s presence in Alberta was a plus on multiple fronts: his proximity and connections to the Valley, his technical background, and his corporate development background. He had also already gotten a commitment from BDC for $20M to raise a Seed fund in Alberta (in what was SpringBank TechVentures)… as Shawn said (and shared with me at a VC event a few years ago). BDC’s Brian Elder, who happened to be based in Alberta, told him to go meet Chris, and that was how he ended up joining that team.

And Chris was open to this as he was playing Moneyball for VC team building. He was bringing in partners that LPs in Quebec and all of Canada would love to back.

Francois provided MSBi with solid back-office relationships for their Quebec LPs, while John brought U.S.-based venture capital experience, a New York/U.S. co-investment network, and America Family office connections. Shawn had a keen technical background and a Corporate Development background, and because he was in Alberta, that made them eligible for some regionally focused LP funding. 1+1 made 3 with each addition.

Chris retained the team that had joined MSBi up to this point, but these key additions brought MSBi to the next level. So, remember that quote from Francois at the beginning of this section and in my First post? Again, I 'creatively' edited it for effect. Here is his full quote.

In 2007, I took a leap of faith and joined a small venture capital fund called MSBi Management, which, back then, invested in life sciences and semiconductors. And when I say a leap of faith, I’m not kidding. The team was preparing to raise a second fund, and if it didn’t work out, they would not be able to afford to keep me on the payroll. It was that simple...

Well, that year turned out to be great; we changed our name to iNovia and ended up raising a $112M fund…”

So, how did Chris and that team reach $112 million? From a $20M BDC anchor cheque?

That fund was raised in late 2007, almost two years after the BDC commitment. Chris slowly cajoled and convinced his previous and new backers to join the fund. And each of those partners was given a good reason to do so. From AVAC (as the precursor to Albert Enterprise), Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ), (previously discussed) FIER Partners and of course BDC. A dozen othe investors were also in there who chose to remain out of the present release.

This is the process Chris alludes to when he talks to everyone at StartupFest about the genesis of iNovia. When you discuss the process, he is very generous, praising all those backers who helped him get it over the line. Without any one player contributing, the fund probably would not have come together.

However, the fund was oddly (or perhaps not) called iNovia II, and all of the Partners there at that moment in time are today referred to as 'founders' of iNovia, because, without any of them, I'm not sure Chris (and Mark) could have pulled this off.

Why was it called iNovia II, rather than iNovia I? Because Fund 1 in everyone’s mind was the 2004 $20M tranche of institutional money that came in after MSBi's initial round, it was where Chris could showcase their investment capabilities, which had great early promise —that was the track record.

But iNovia II was a coup.

To put the coup in the context of how amazing it was, in 2008, iNovia raised $107M ($5M showed up a few months later), when all VC funds in Canada raised only $1.08B—no other first-time fund focused on seed or Series A raised that much again until 2018.

OR In 2008, approximately 10% of all LP investments in Canada went to iNovia, which was, I’ll argue, a brand-new fund at the time. You might say it was not, but iNovia, the company, was founded in 2007, and most of the senior team was brand new.

Today, iNovia has several billion under management and is the anchor tenant in the Quebec venture ecosystem and, to the same extent, in Canada. At the same time, Chris Arsenault, Shawn and other several of the cofounders, still run the place. No other fund in Canada plays at almost all levels of Venture Capital like they do.

They made a video on their 15th anniversary that is fun to watch. I do recommend it.

Many other Seed and Series A funds emerged following the iNovia raise.

However, this team led the new generation of Canadian Venture funds, giving rise to names across Canada that we all know today. Real Ventures, Whitestar, Golden Ventures, VersionOne, Build, Garage, and others can thank iNovia for demonstrating the veracity of the story that backing new managers in the early stages in Canada can be a winning formula. An argument that is increasingly less popular today.

However, when Chris shared his own story and stated that it took about two and a half years to raise what we call iNovia, he didn't mention MSBi or the Brunet report once.

Legacy and Impact on Canadian Venture Capital

However, the Brunet Report served as a catalyst that led to the establishment of many of the local and national venture institutions that Canada has today. You may think this is a Quebec story, but each ecosystem released reports after Brunet and took learnings from Quebec.

Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Alberta, British Columbia, and to some extent Ontario all took the Brunet report in hand, using it to develop and release local versions in the following decade. The Federal government used it as an outline for the Jenkins report, which catalyzed a more national innovation and venture capital strategy. Twenty years later, it is a document whose influence is still being felt.

However, like all historical events, particularly in Canadian tech, it is rarely read or reviewed.

Ask people in Quebec, and they’ll tell you the Brunet report is the reason why Quebec emerged from the financial crisis with a robust venture market. And in the case of Teralys and other pillars of the community, I’d agree.

However, an often-forgotten lesson is important because the lynchpin of the iNovia journey was a commitment from the BDC to anchor the fund. Not the programs Quebecers today point at.

Quebec’s implementation of the Brunet report failed its early-stage market. It required the BDC to try first through the Go Capital initiative and then through direct LP cheques to help. Quebec often forgets about that key point. Going forward, they should try to fill that gap themselves.

Some thoughts on the BDC’s role today

That program that BDC announced in 2006—which catalyzed iNovia—had not progressed significantly by 2008, when a financial crisis impacted both BDC and the rest of the world and led to its quiet shelving3. Unsurprisingly, BDC was dealing with a mess (and that is a story for another day).

However, following a 2009/10 internal review of their venture capital efforts, BDC looked back and realized that this initiative to fund the early stage through LP cheques rather than a direct fund (Go Capital) made a lot of sense. iNovia was often discussed internally and externally as a clear example of an apparent, unencumbered success.

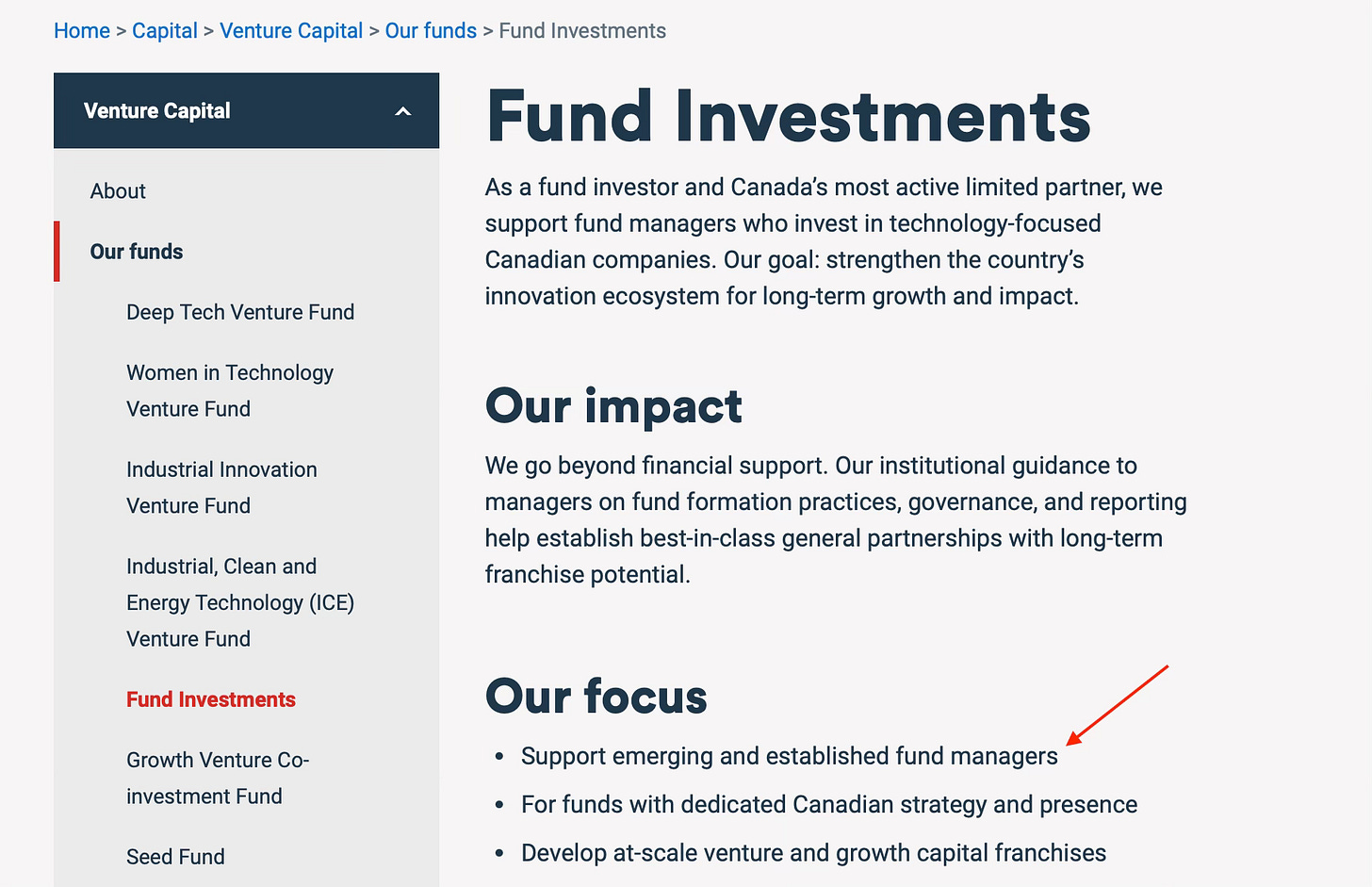

So, in early 2011, BDC established a new group to double down on the iNovia lessons. It was initially known as Strategic Initiatives and Investments and later renamed several times. Regardless of the name, its stated goal and intention were to support and help build the early-stage market in Canada through direct and indirect methods.

Some of those efforts were LP cheques to emerging or small fund managers whose names you might recognize. VersionOne, Real Ventures, Golden Ventures, Garage, Mistral, Rhino, Brandproject, Gibraltar, Tandem Launch, Build Ventures and McRock. There were others. All of these were focused in line with the goals of this program, which was to build an independent ecosystem in the early stage.,

Not all names were successful, but all contributed to the ecosystems they focused on and leveraged the support of the BDC to raise larger funds.

However, this program was quietly merged with the Fund of Funds group in 2015/16, and the focus shifted. Today, you won’t find the Fund of Funds group seriously considering any funds with targets under $50-80M, something they were happy to consider in the early 2010s.

That Strategic group also cut cheques to early-stage companies at select accelerators. Here is the team’s VP, Senia Rapisarda (who never ages, it seems, and now runs Harbourvest Canada), talking about the group back in 2013:

In the video, Senia discusses 40 (pre) seed deals at $150,000 a pop, which amounts to $6 million, not a massive amount of money, but impactful for those companies. This program was also shelved in 2016/17.

So Canada’s BDC has seemingly refocused on what the ‘D’ stands for. And what does the D stand for? BDC—in English—is the BDBC—the Business Development Bank of Canada. It's got a long and interesting legacy, but for this discussion, the “D” in its name is essential because it is now the topic of discussion by my industry peers and others.

Like many crown corporations, it is a creature of a Parliamentary Act. Thus, it undergoes a periodic legislative review every ten years. The most recent one was done in 2023, covering the period from 2010 to 2022. It’s an interesting read. However, there are two issues: the expansive timescale in the review, which is pretty huge at 12 years and this:

Further, the BDC launched its Strategic Initiatives and Investments group during the review period, and mandated it to stimulate the venture capital and innovation ecosystems. Specifically, the BDC's objectives were to highlight the success of underlying technology business in Canada; enable and attract future investment and value-added support for these businesses; and, demonstrate the viability of the Canadian venture capital industry and attract further capital into this asset class.Footnote 43

As the VC industry gained momentum in Canada, the BDC adjusted its VC strategy to reinforce the Government of Canada's priorities, including a greater emphasis on supporting diversity and emerging sectors. In addition to increasing investments in the ICE Fund, the BDC launched the Women in Technology Venture Fund in 2017, which represented the largest VC fund at the time focusing on women entrepreneurs in Canada.

These two paragraphs are essential, as the first paragraph directly covers the conservative government's mandate of 2010-2015, and the liberal government’s 2015 onwards is covered in the second one. The adjustment between those paragraphs turned off BDC’s focus on investing in early-stage companies and first-time GPs as a strategic consideration.

Frustratingly, the Legislative Review uses footnotes in its Review that reference a government report that you and I can’t read. (footnote43) It was written by a firm that was asked to write it for only this use case, and it is the only report not publicly available. Why, your guess is as good as mine. But why should a public legislative review about the BDC's role in VC hang on a report you and I can’t read? That’s a question for another day. (or an access to information request)

The BDC legislative review (and if you’d like to, it's worth reading) acknowledges declines in market conditions (as it went to press in early 2023), and BDC’s response to the review was to introduce a “legislative review action plan”, in which they also announced their $50M Seed Fund.

Again, they did not discuss or review anything for the first time or small emerging managers outside their diversity commitments. The Review effectively said the BDC didn’t need to address this. However, an emerging manager in 2010 was significantly different from what it is today, and only someone with market experience might catch this. And I don’t think the average VC observer understands that difference.

If you, like me, believe iNovia Fund 2 (was Fund 1), then by the BDC’s definition of an emerging manager, iNovia continued to be an “emerging manager” until their fourth fund or the fund that they raised in 2017—nine years after the events I’ve catalogued here. In 2018, I once congratulated (jokingly) Chris Arsenault on a VC panel on no longer being an “emerging manager. " No one else got the joke.

But if Chris were approaching the BDC today, I doubt he’d get the reception he got in 2006. The BDC has decided they are not needed as a catalyst cheque for the first time or GP’s addressing the seed fund market segment.

But the iNovia team sees an opportunity in the problem I’m discussing, as:

Inovia partner Karamdeep Nijjar put it. “We also understand that investing at those really, really, really early stages is an art on its own, and there are people that are as well suited—if not better suited—to do that,” Nijjar told BetaKit in an interview. “For Inovia to thrive long term, it has to work within an ecosystem that is well-supported and has a lot of interesting folks doing interesting investing at stages earlier than us.”

I don’t think Karam could have better presented the case for stronger (BDC) involvement at the early stage. But subsequently in the same article, he did:

Nijjar argued that while there are some institutional VC funds in Canada doing a good job of backing pre-seed startups at scale, the country could use more of them. From his perspective, more diversity in terms of funding sources will ultimately lead to better outcomes.

“This is a pretty unique asymmetrical bet we can take,” said Nijjar, pointing to its low-risk, high-reward potential. While he said the Discovery Fund is unlikely to generate strong short-term results, over the longer term, it could have “a dramatic impact” on both Inovia and the ecosystem at large.

This should be a polite wake-up call to my friends and former colleagues at the BDC. I used to work there and often wonder why only iNovia is looking to support the ecosystem with a small but impactful fund program for early-stage focused GPs?

It's incredible how the world turns here.

iNovia, the Fund, which was anchored by a forward-thinking Fund of Funds leader back in 2008, is now doing the job the BDC did for them by mentoring and catalyzing the next generation of managers. Keeping the ecosystem moving. I’m sure they would love some company.

The ACELP founders are much more circumspect on all this.

Shout out to Brian, the first LP to tell me never to become a GP in Canada. He was more right than he knew!

Vanedge Fund 1 commitment came out of this envelope but closed late - in 2010. Someone told me they believed Tandem Expansion was part of this, but someone else told me, “Not so.” It certainly looks like it was out of a different program. But I’d love a clarification!

The power of meeting the right people at the right time is magnified a thousandfold in the VC ecosystem - with lasting impact countrywide even decades later!