No ‘Real Venture Capital’

Part 1 - Quebec’s Venture Capital Ecosystem 1990-2003

From my last post on the retreat of the Canadian Pension Plans from the Venture ecosystem during the 2000-2010 decade, and the subsequent collapse of Venture Capital in Canada, one clear contrast emerges. Quebec's venture ecosystem's relative health and strength compared to the rest of Canada.

Over the next few posts, I plan to tell an entertaining story about the twists and turns in the Quebec ecosystem over the past 30 years. Quebec is an interesting study for the rest of Canada. Many of the stories are not widely known, and I think they need to be shared somewhere to reach a whole new generation of emerging managers who are entering the Canadian Venture ecosystem.

I’m not alone; take, for example, this (edited) email from a Quebec-based VC Analyst who asked a question about my last post.

Hey Matt,

You said that –

"By 2007, only $1.19 billion had been raised by Canadian V.C. funds, and 70% of that new capital for V.C. funds had gone to only Quebec-based organizations."

Was this because CDPQ jumped into the market to save Quebec after they all left? It doesn’t look like there was a lot of Venture Capital in the market before then…

What's fun was as this email came in, I was watching a video of a Quebec V.C. reminiscing about the same year - here is what he said:

In 2007, I took a leap of faith and joined a small venture capital fund called MSBi Management. Back then, the fund invested in life sciences and semiconductors. And when I say a leap of faith, I'm not kidding.

The team was preparing to raise a second fund, and if it didn't work out, they could not afford to keep me on the payroll. It was that simple.

2007 was a pivotal year for Venture Capital in Quebec and Canada. If you want to understand the makeup of our Canadian Venture Capital ecosystem today, for better or worse, you should start in 1990s Quebec. This was the crucible moment where significant lessons were learned in Quebec and shared with the rest of Canada. Were they the right lessons? I’ll let you decide.

So let's dive into the history. Like all things historical, it's surprisingly timely and more pertinent today - as I'll show.

Maître Chez Nous

In my mid-20s, I sat at a table with the (now late) former Prime Minister, Brian Mulroney. He confided to us (paraphrasing) that when the President makes an address to his nation, everyone in Canada listens. But in English Canada, we're listening to the American President, while in Quebec, they’re listening to the French President.

This insight pays dividends when understanding the differences between how Quebec approaches economic solutions and how the rest of Canada does.

That unique way of solving problems leads to knee-jerk responses to any 'Quebec solution.'

Quebec is different, but I'd like you to consider that difference from a slightly nuanced angle. The main problems you're trying to solve if you're a political leader in Quebec are roughly two things:

Your people are culturally (and importantly linguistically) a minority within the country of Canada.

You are not a nation, well, not legally. And many of your citizens are Nationalistic and want to be a nation or treated like one, whatever that means...

Of course, if you're a Quebec political leader, you have other things to solve, like healthcare, building bridges, etc. But you have these two things I mentioned that differ from anywhere else in Canada.

So Quebec, after its 'quiet' revolution, decided to solve its first problem by promoting the Quebec language and culture.

But how do you act like a ‘Nation’? Let's examine the second point using a clear policy decision example. When Canada started the Canada Pension Plan (CPP), what did Quebec do?

It can be summed up by that excellent picture I stole from Wikipedia, Maîtres Chez Nous. It means quite literally "Masters of our House."

They wanted Quebecers (ideally the French-speaking kind) to be in charge of Quebec, in politics, culturally, and economically. So, they also started to build parallel institutions for Quebec that looked much like Ottawa had built for all of Canada, but were different.

Quebec opted out of CPP and created CDPQ. But it wasn't trying to be a Quebecois CPP. It was modelled on the Caisse des dépôts et consignations, France's state Pension Plan. This statement on its goals at inception spells it out... (French first, then English below):

Les intérêts des Québécois ne s'arrêtent pas, après tout, à la sécurité des sommes qu'ils mettront de côté pour assurer leur retraite. Des fonds aussi considérables doivent être canalisés dans le sens du développement accéléré des secteurs public et privé, de façon à ce que les objectifs économiques et sociaux du Quebec puis- sent être atteints rapidement et avec la plus grande efficacité possible. En somme, la Caisse ne doit pas seulement être envisagée comme un fonds de placement au même titre que tous les autres, mais comme un instrument de croissance, un levier plus puissant que tous ceux qu'on a eus dans cette province jusqu'à maintenant

Or in English (my emphasis)

The interests of Quebecers do not stop, after all, at the safeguarding of the amounts they will put aside to ensure their retirement. Such considerable funds must be channelled toward the accelerated development of the public and private sectors so that Quebec's economic and social objectives can be achieved quickly and with the greatest possible efficiency. In short, the Caisse must not only be considered as an investment fund like all the others but also as an instrument of growth, a more powerful lever than all those we have had in this province until now.

You might call this socialism, and most of us in English Canada do. But if you're nodding and thinking, 'This is socialism,' and you're sitting in Alberta, I'd be careful about that glass house you're sitting in.

"We've never faced a more hostile situation coming from the central government."

"This is a new moment in our history."

The report explaining why, which was released at the time, is pretty straightforward, (my emphasis):

"Create an Alberta Pension Plan offering the same benefits at lower cost while giving Alberta control over the investment fund." "Legislation setting up the Canada Pension Plan permits a province to run its own plan, as Quebec has done from the beginning. If Quebec can do it, why not Alberta?"

It seems Alberta is taking a cue from Quebec—it wants to be the master of its own house.

So, while Alberta is changing its stripes, from the beginning, Quebec has believed this to be economic nationalism—not socialism (though that line is sometimes very fine). They're taking their own money and investing it in themselves, with professional managers who look at the holistic approach for both the actual returns and the economic development of the home province of the investors themselves.

What is the name of this? Quebec Inc.

For example, the City of Montreal gave Bombardier its initial push into mass transit markets in the early 1970s by awarding it a contract to build subway cars. Had they done this before? Nope. So, who funded that? - the provincial government.

Desjardins, a local credit union, was instrumental in saving food giant Culinar Inc. of Montreal from a U.S. takeover during the same era.

The Caisse (CDPQ) was crucial in financing dozens of now gigantic provincial companies, from Le Groupe Videotron to Alimentation CouchTard (Circle K).

Why does Quebec Inc. do this? In their view, being dependent on the rest of Canada or Ottawa to invest in Quebec is the antithesis of being a Nation.

So, after failing to become a separate nation in a referendum in 1980, Quebec political leaders did and continued to promote Quebec's economic policy: to build and germinate ‘strong local champions' that can compete internationally.

But how better to build those champions than with the magical fairy dust of Venture Capital?

The 90's

Have a coffee with a Quebec fund manager or a L.P. and ask them about the local ecosystem in the 1990s; most will say Quebec's V.C. industry was smaller than the rest of Canada. If they're under 40, they might even tell you there wasn't a Venture Capital industry in Quebec before 2010 or so.

Even Investment Quebec has this quote on its website for the period (from 2022):1

“Il y a 20 ans, il existait bien peu de chose en capital investissement au Quebec, rappelle M. Leroux. «Il n’y avait pas d’écosystème structuré. À part les anges investisseurs, les entreprises qui avaient besoin de capitaux pour innover n’avaient personne vers qui se tourner.”

In English:

Twenty years ago, there was very little venture capital in Quebec, recalls Mr. Leroux.

"There was no structured ecosystem. Apart from angel investors, companies that needed capital to innovate had no one to turn to."

That would be a unique way to look at it because of the numbers in the Quebec ecosystem posted during this period. Those numbers show that in the 1990s, Quebec was actually Canada's centre of venture capital.

As this chart shows, Quebec consistently outperformed Ontario in the amount of Venture Capital investments—the chart also explains why. The Venture Capital industry was government-made, and the Quebec Government and Quebec Inc. directed tons of money into the market.

Canada was wracked by a massive recession in the early 1990s, and you can see what that did to Venture Capital in the Province of Ontario (the darker gray boxes).2 Meanwhile, in Quebec during the same period, Venture Capital thrived. Intuitively, it should not have been the case…

After that recession, Quebec's separatist provincial government held a second referendum to leave Canada (in 1995). This led to a flight of Canadian domestic and international investment, which hit Ontario's numbers. Then we had the now forgotten, massive (but short-lived) Asian Financial Crisis. However, none of these things were particularly noticeable in the Quebec Venture Ecosystem stats, but they were for Ontario (go back and look at that chart).

Why was Quebec so immune?

The quick answer is that there was a flood of cash into Quebec in the 1990s – most of it venture capital, and when I say flood, it's on a biblical level, as one academic put it:

V.C. showed a 450% increase between 1994 and 2003. Such drastic growth would not have occurred without an even greater increase in the provision of government-backed V.C. Between 1995 and 2002, while total public resources (including tax expenditures) dedicated to business support grew by 283%, including an impressive 1511% increase in the value of equity shares acquired by Quebec's state corporations in the province.

So Quebec's total investment in "Venture Capital" grew 4.5x in just over ten years.

But let's look at what was happening on the ground during these years… I don't think stats describe it.

From the article above:

When the idea of the Solidarity Fund came up during the recession in the early 1980s, Mr. Blanchet was an enthusiastic backer.

Tired of waiting for politicians and businesses to ease high unemployment, the Quebec Federation of Labour decided to launch its own worker-financed scheme to keep businesses from going under.

"We're looking for small businesses which are just getting started or have been around for a few years and need a capital push," said Blanchet. "It's the ordinary guy we want to help, not the fancy high-tech company which can find funding from many other sources."

This is from the article with Claude Blanchet (above), whom I'd love to have a beer with one day. When the article was written in the early '90s, he had over $330M in venture capital investments in Quebec. However, the article also defines the V.C. goal in the minds of the capital allocators at that time. The title mostly nails it—Venture Capital wasn't to grow fast-growing businesses but to "keep firms alive."

In effect, they were interested in solving fundamental business issues using equity investment—the discussion on returns is noticeably absent or undefined – the investment was the goal – the divestment was not considered. As one L.P. from these years said to this intrepid author, "Venture Capital in those years was, in some ways, Venture Socialism" (or Nationalism).

This fund is of course still around today. You'll know it as FSTQ (Fonds de Solidarite - FTQ). And if you read that article, you'll see why it was able to raise all that money - tax breaks. If you invest, have a certain income level, and hold for a period, you can get up to 80% of the investment back on your tax return. You then also have this investment in "venture capital." So even if those deals lose half their net value, you are, in the end, still up on the investment because of that generous tax break...

This is the (basic) math of the "Labour Sponsored" Funds. In some future posts, I'll dive into their history (probably when I write about the history of Ontario). However, a fair chunk of venture capital in Canada from 1985 to 2010 was from investments of this type. Did they perform? A better question might be, did they need to?

In the article shared earlier you can see that tension. When Venture Capital is being used to do something other than drive growth, what is it? This is the first major lesson from this period.

There were other lessons to be learned, and Quebec had other mechanisms to drive V.C. money. Separately, they started dozens of what we would recognize as seed funds, which made up the bulk of venture capital in the province.

This always seems to surprise people… I sat down with the Partner of a seed fund at Place Ville-Marie this past summer, and she told me that pre-2010 or so, there were no early-stage fund managers in Quebec. But in 1999, there were over 20 firms with AUM under $50M; all focused on initial Cheques below $2M, which we'd all call seed today.

Let's look at a few of them. I’ll have more data on this later.

I love this quote; it captures the spirit of the time - and just who was running these funds, from the Toronto Star in 19943:

In Canada, most venture-capital funds are either run by governments or large financial institutions. The idea of Prytula tooling around Quebec in his 1986 Toyota Cressida - clutching his car phone and looking for companies to invest in - doesn't fit the stereotype. But venture-capital funds have become a grass-roots industry in Quebec. Many such operations are run out of store-front offices in small towns where business people can just walk in and make their pitches.

Richard Prytula ran a $40-million venture capital fund called Technocap from his car (he also eventually had an office). Today, you can visit Technocap's website (it's still online, and it was last updated in 2009). Richard raised his funds from CDPQ, Bombardier Trust, Solidarity Fund QFL, Desjardins Pension Funds, National Bank of Canada, and TechnoAnge Inc. – All deep Quebec Inc. names.

Or this other Seed fund from the Montreal Gazette (1999)4:

"Many of these young companies, even with a great plan well spelled-out in front of them (by a consultant), lack the ability to execute the plan, so it's not only the conception of the proper business model that we offer, but the execution of that plan, as well. We help them grow and we carry the bag for them at the same time, and we do it collectively with them and their team. When our mandate is exhausted or when they're well on their way, then we can step out and the company can then attract talent to fill the key management positions."

Forbes Alexander plans to invest between $100,000 and $500,000 in seed money in three to eight companies per year, primarily in the Internet, electronic-commerce, enterprise software and Internet-telephony fields.

There are at least a couple dozen examples of firms that sound very much like seed funds today. Like this one:

So by the year of the Dotcom Boom peak, in 2000, Quebec accounted for nearly half (49%) of all venture capital deals in Canada (Ontario was at 31%). This represented about 1.3% of Quebec's GDP.5

To give you a mind-blowing way of looking at this, the United States's V.C. industry represented 1.045%6 of GDP in the same year, meaning there was 25% more Venture as a % of GDP in the province than there was in the U.S. (in the year 2000 and at the height of the dotcom bubble).

Comparing how much Venture cash was available in Quebec vs. the rest of Canada, they had almost three times the amount invested per person that year.

So wait, you must be thinking...

"Quebec was a bigger V.C. market than America in the year 2000 on a per cent of GDP?!"

Yes.

And "In 2000, for every person in Quebec, there was three times more V.C. invested than for every person outside of Quebec?!"

Yes.

But in Quebec today, the entire Province suffers from collective amnesia of this period; remember that translated section from (French) Investissement Quebec (I.Q.) website talking about this period (it was posted in 2022):

Twenty years ago, there was very little venture capital in Quebec, recalls Mr. Leroux.

"There was no structured ecosystem. Apart from angel investors, companies that needed capital to innovate had no one to turn to."

Obviously, this isn’t true…

Bad Memories…

Or is it?

In some ways, Mr. Leroux may be right. In some ways, Quebec did not have very much venture capital. So how can I spend a whole post writing this history explaining that there was a vast V.C. industry and then turn on a dime and say there was not…

Let me share some more numbers. I'll be bouncing around with different graphs to tell this part of the story, so bear with me. The charts look a bit different in each iteration, but they tell a fantastic story.

Let's start with that earlier chart that shows Quebec's dominance of Canadian Venture:

As I've explained, Quebec was dominated by early-stage funds in the 1990s. You can see it in this graph, which, unhelpfully, I had to colour for you: The orange line is Quebec. Quebec dominates in the sub-500 K deals. The second smaller bar graph is Ontario; the rest is rounded out by B.C., the prairies, etc.7

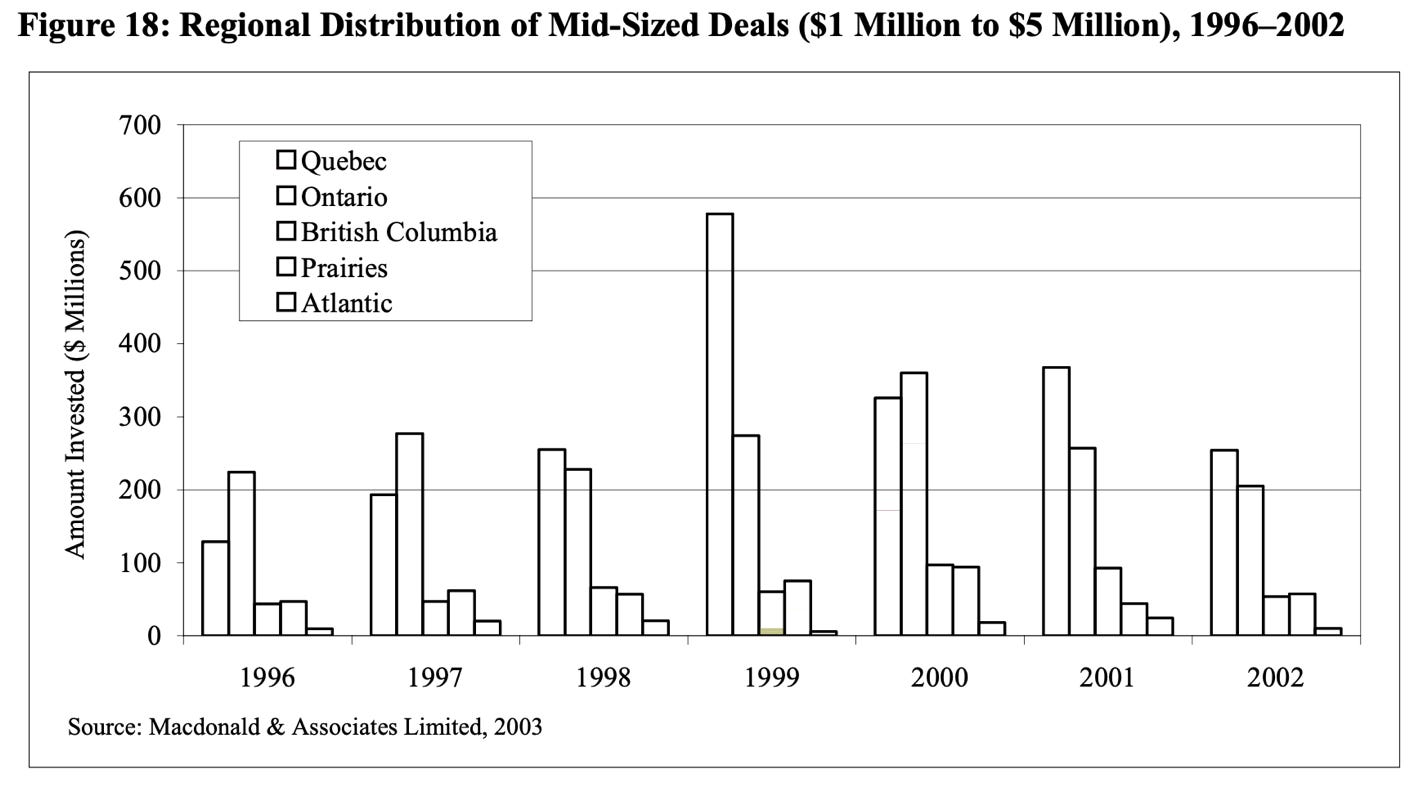

As the round sizes grow, look what happens. Same order... for $1-5 M, the Quebec lead narrows.

Here is the money shot. It's in the same order. For some reason, I found this one in colour for you.

See the problem?

During these years, Quebec dominated the rest of Canada in the smaller investment categories under $5M. But in rounds over $5M, Quebec is fighting for distant second place and almost being beaten by British Columbia (!). You might wonder how this can be—notably after I showed that so much venture capital was available in Quebec in 2000.

So what is going on? The 2003 report,8 where I got some of these charts from scratches its head:

Until 1998, Quebec dominated the Canadian VC scene, as measured by number of deals, deal size and capital invested. Since 1999, Quebec has continued to exceed the other provinces in terms of number of deals, but has fallen behind in terms of deal size and capital invested.

The same report later thinks it could be a life sciences problem:

Given Quebec’s strong focus on life sciences firms, it is hard to explain this lower average deal size, since normally the emergence of life sciences firms’ higher capital requirements should lead to larger deals. VC in Quebec tends to involve many small transactions, which lowers the average deal size. More information on the capital needs of life sciences firms would help to determine whether there is a size gap for this sector in Canada, particularly given that the average VC deal for U.S. life sciences firms was much higher (C$16 million in the U.S. compared to C$2.7 million in Canada in 2002).

Two things are happening, and reports at the time allude to but does not directly engage with the data.

Those seed investments generally did not graduate at the same pace or went nowhere. Quebec had a robust Seed market, and the government primarily focused on company creation as a measure of success in entrepreneurship in the province. (this is a lesson that Quebec and others have never seemed to learn from).

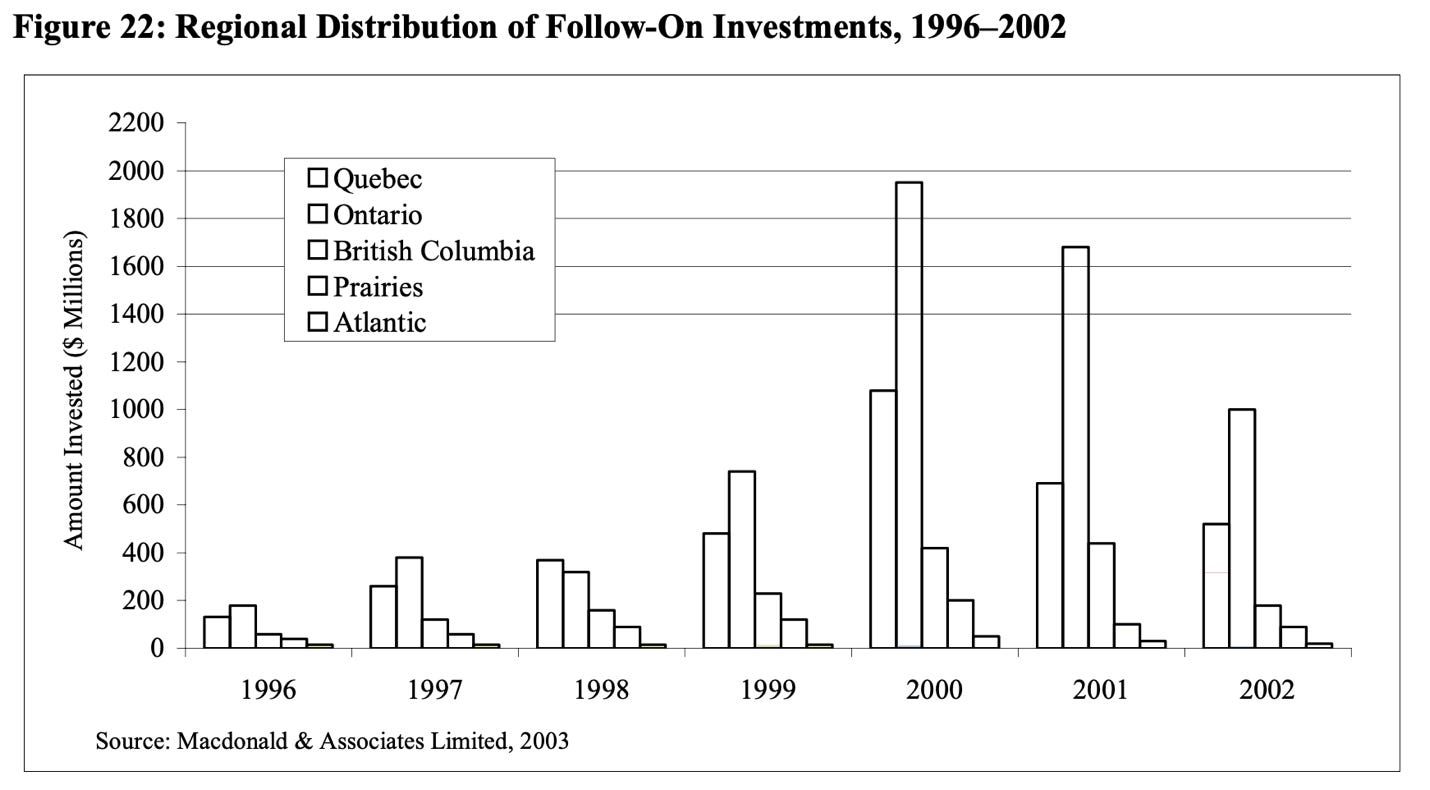

The province had few funds for them to graduate and get further investment—in what we would call today Series A or B (round above $3-5M-ish). As you can see in this helpful chart, follow-on investments for Quebec-based companies just never showed up. (again, the first bar graph in each is Quebec, followed by Ontario, etc.)

You would have thought that with such a robust seed market, there would be a compensating large influx of capital from later-stage investors into those seed companies, but that wasn't happening.

Meanwhile, Ontario, with a much smaller seed market, had a much more follow-on investment dollars than Quebec.

Secondly, companies in Ontario raised more capital at an earlier stage, and crucially, they raised from local VCs AND U.S.-based funds. This is best shown and described in one of the most off-topic and funny episodes of 'Who Gets a Direct Flight to the Valley in 2000?'

Nothing Direct

This was front-page news in the business press in Ottawa and Montreal.

Air Canada, which was headquartered in Montreal, chose, as a surprise, Ottawa - a city with a population that was a third of the size of Montreal but that could justify more business travellers and reasons to fly to the Valley than Quebec's entire tech ecosystem and home to almost half of the V.C. investment in Canada. If all those seed fund managers in Quebec wanted to fly directly to Silicon Valley, they had to drive or fly out of the province to Ottawa to get their closest connection to Silicon Valley.

Nothing shows how disconnected Quebec was from the North American capital flows during this period than this.

So, you could say Quebec had little "real" Venture Capital.

The vast majority of it came from Quebec government players making Quebec investments into Quebec companies, and if that wasn't happening, it was being done by Quebec-based fund managers who got their funding from Quebec Inc. No one outside of the province was coming to join them in their Venture Ecosystem.…

By 2003, there was no escaping that reality.

over the period from 1993 to 2002, the Quebec government injected $4.6-billion in risk capital to finance businesses. Almost 80 per cent of that amount was injected between 1998 and 2002 at the height of the PQ's interventionist policies. "The heavy losses they [government-owned venture capital corporations] have recorded have placed additional strain on Quebec public finances.

And

Earlier this week, Finance Minister Yves Séguin projected that the government-owned venture capital corporation, Société générale de financement, will incur a minimum loss of $644-million from 2003 to 2005 due to bad investments. "Our examination of the losses is not over because there are others on the way," Mr. Séguin said in the National Assembly yesterday in response to PQ Opposition attacks.

The dot-com crash led to a moment of stark reality. Venture capital had become, to borrow a quote - “a costly endeavour”. Over the next few years, Quebec institutions would write off over $3.5B of their venture investments.9 How much of that was what you would call venture?

And that is lesson we could all use today, in Canada there are dozens of what are now being quietly described as ‘Venture Capital Plus One’ Funds or as one senior federal bureaucrat described it to me recently:

“They’re venture funds, they’re returns driven - but they’ll also meet another mandate that is not about those returns.”

There is a tension there, and the lesson from Quebec in the 1990’s was that, that it rarely works.

But for those in the early 2000’s, the lessons from all those charts were a stark reminder that Quebec needed to get serious about its Venture ecosystem because no one else was taking them seriously.

In the next post, I’ll discuss how Quebec decided to get serious.

This quote will be used again and a few times in Part 2… its got some nuance I want to discuss. To be fair I don’t think Benoit is wrong here. But I need a good quote to launch the discussion.

This chart is from “Small Nations, High Ambitions: Economic Nationalism and Venture Capital in Quebec and Scotland” by HUBERT RIOUX - which is a great read to nerd out on this and I agree with some but not all of his thesis. I liberally grab some stats from him throughout this.

The Globe and Mail, Apil 1 1991, B3,

The Mtl Gazette, Nov 24, 1999, D1

pg 41 of “Small Nations”

NVCA from this report: https://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10234/203015/TFG_2023_Martin_Graterol_MiguelAlejandro.pdf?sequence=1

these chart are from this report: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/Iu4-57-2002E.pdf

https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/Iu4-57-2002E.pdf

This number is probably a best guess, and underestimated, it was discussed at aCVCA confernce in 2009

Did you title your post in a way that maximizes SEO for "Real Venture(s)"? JK! ;-)

Amazing. Looking forward to Canadian VC vignettes!! Are you going to do BC?